CLIO Talks Back

Karen Offen

United States

Archive

- Jun 2011

- May 2011

- Apr 2011

- Mar 2011

- Feb 2011

- Jan 2011

- Dec 2010

- Nov 2010

- Oct 2010

- Sep 2010

- May 2010

- Apr 2010

- Mar 2010

- Feb 2010

- Jan 2010

- Nov 2009

- Oct 2009

- Aug 2009

- Jul 2009

- Jun 2009

- May 2009

- Apr 2009

- Mar 2009

- Feb 2009

- Jan 2009

- Dec 2008

- Nov 2008

- Oct 2008

- Sep 2008

- Aug 2008

- Jul 2008

- Jun 2008

- May 2008

- Apr 2008

I.M.O.W.'s debut blog, Clio Talks Back, will change the way you think about women throughout history! Be informed and transformed by Clio Talks Back, written by the museum's resident historian Karen Offen.

Inspired by Clio, the Greek muse of History, and the museum's global online exhibitions Economica and Women, Power and Politics, Karen takes readers on a journey through time and place where women have shaped and changed our world. You will build your repertoire of rare trivia and conversation starters and occasionally hear from guest bloggers including everyone from leading historians in the field to the historical women themselves.

Read the entries, post a comment, and be inspired to create your own legacies to transform our world.

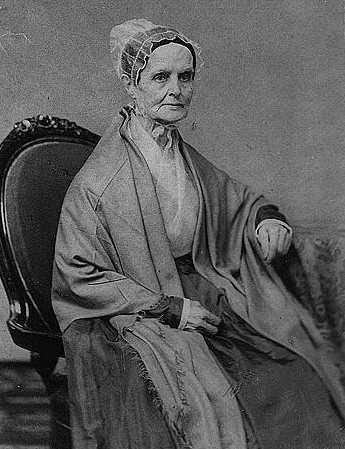

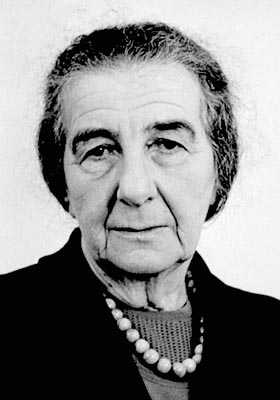

www.knesset.gov.il

Golda Meir's official Knesset portrait

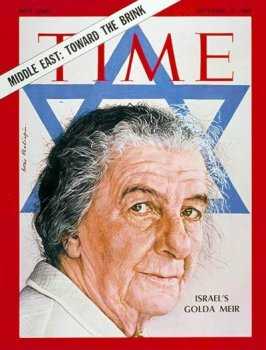

Google images

Golda Meir on the cover of Time Magazine

Clio remembers the contributions of Golda Meir as Israel?s Minister of Labor

2008-09-30 14:52:22.000

Most people know Golda Meir (1898-1978) as the first women to serve as prime minister of Israel, from 1969 to 1974. She was 70 years old when she agreed to take that high office and a seasoned political figure. She already had a long and distinguished political career as leader of the Histadrut (Israel?s General Federation of Labor), deputy to the Knesset (Israel?s parliament), Israel?s first ambassador to the U.S.S.R., Foreign Minister, and as Minister of Labor. She also had three children.

Golda Meir was less interested in her appearance than in what could be done to ensure success and survival for the State of Israel. She writes eloquently about her commitment to her newly-established country in her autobiography, My Life (1975). We know a great deal about her leadership as well as her ability to raise money and arms for Israel abroad, and especially in the United States, where she had grown up. What is less known is her contributions to building up Israel?s remarkable social support system, especially as it affected women ? both Jewish and Arab ? who lived in Israel.

Here Golda Meir speaks in her own words about her concerns and actions for social justice:

As I write about that period in my life, I can?t help reflecting on how lucky I was to have been in on the beginnings of so many things ? not that I influenced the course of events, but that I was so much a part of what was happening all around me, and sometimes my ministry and I were even able to play a decisive role in the upbuilding of the state. I suppose that if I were to limit myself ? as I must ? to singling out the two or three developments that were the most rewarding and most meaningful for me during those seven years, I would have to start with the legislation for which the Ministry of Labor was responsible. For me, that, more than anything else, symbolized the kind of social equality and justice without which I couldn?t even imagine the state functioning at all. Old age pensions, widows? and orphans? benefits, maternity leave and grants, industrial accident insurance, disability and unemployment insurance were essentials in any self-respecting society, and whatever else we lacked or postponed, these were basic.

Even if we couldn?t afford to cover all of the labor movement?s achievements by law at once, we were at least duty-bound, I felt, to legislate as many as possible as soon as possible, and it meant a great deal to me to be able to present Israel?s first National Insurance Bill ? based largely on the voluntary insurance schemes of the Histadrut [the Labor organization] ? to the Knesset in January, 1952, thus paving the way for the National Insurance Act that came into effect in the spring of 1954. National insurance wasn?t a magic remedy. It didn?t eliminate poverty in Israel, or close the educational or cultural gap between our citizens, or solve our security problems. But it did mean, as I told the Knesset that day, ?that the State of Israel will not tolerate within it poverty that shames human life, the possibility that the happiest hours of a mother?s life will be marred by worry about food or the possibility that men and women who reach old age will curse the day they were born.? A drain on our resources? Of course it was ? which was why we had to do it in stages. But it had economic as well as social significance and the merit of accumulating capital and withdrawing money from circulation, which helped us fight inflation. Above all, it equalized the financial burden, made one age group responsible for the other and spread the risk. It also had another by-product that mattered to me: Because the percentage of babies born in hospital rose as a result of the maternity benefits (which included the cost of hospitalization), infant mortality ? which was high among the new immigrants and the Arabs ? dropped. I went to Nazareth myself to hand the first check to the first Arab woman who had her baby in a hospital there, and I think I was more excited than she was.

Source; Golda Meir, My Life (New York: G. P. Putnam?s and Sons, 1975), pp. 275-276.

For more information: http://www.zionism-israel.com/bio/golda_meir_biography.htm; http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ma-Mo/Meir-Golda.html

Google Images

Group photo of women who organized the 1908 All-Russian Congress of Women

Courtesy of Marianna G. Muravyeva

Organizers & Participants of the 2008 Russian Women's History Conference

Clio Commemorates the 1908 All-Russian Congress of Women.

2008-09-21 10:17:38.000

The year 2008 marks the centennial of the first All-Russian Congress of Women, held in St. Petersburg in early December 1908. This was the first ?women?s parliament? in Russian history. ?Just think,? one contemporary report exclaimed, ?women have organised everything and are running the whole congress themselves. Astonishing!?

Finnish women and men obtained the vote in 1906, in conjunction with their newly autonomous status within the Russian Empire. In late June 1906, the first elected men?s parliament in Russia, known as the First State Duma, also debated woman suffrage, and one deputy presented an eloquent argument on behalf of enfranchising Russian women. The tsar?s government abruptly dissolved the First Duma in early July, so no action could be taken. The Second and Third Duma proved dismissive of arguments for ?equal rights,? amidst the rapidly deteriorating the Russian political situation.

Early in 1908, the women?s conference organizing committee had to submit their preliminary program to the tsar?s Ministry of the Interior for approval ? and those officials initially cut out the ?most controversial? paragraph pertaining to ?the struggle for political and civil rights at home and abroad? and placed severe restrictions on attendance. Students and foreigners were barred from participating. Men could speak but could exercise no voting rights. Nevertheless, 1053 individuals had enrolled by the opening day of the congress. In addition, representatives of the press (including the foreign press) ? and the watchful police monitors ? attended. Many questions were considered ?out of order? and the congress organizers (including Anna Shabanova, Mariia Pokrovskaia, and Anna Filosofova) remained concerned that the police might shut down the congress prematurely if ?forbidden? topics (?the peasant crisis, women in industry, problems of marriage, maternity and morals, women?s suffrage, and the ?organisational tasks? of the women?s movement?) were broached. The threat of government censorship, and the use of force, was very real ? and intimidating. Russian civil society operated under serious constraints. In particular, freedom of speech and association were constantly monitored.

In its final form, the congress program contained four sections: (1) women?s role in philanthropy and ?cultural activity;? (2) women in the economy, family, and society; (3) the political and civil position of women in Russian and abroad; and (4) women?s education. In the last section, delegates enthusiastically endorsed co-education of the sexes and sex education.

One group present, a contingent of 35 working women from St. Petersburg, were (in Linda Edmondson?s words) ?committed to opposing the feminist slogans of the congress, and stressing class war as the dynamic of capitalist society. They were conspicuous, from the very opening of the proceedings, by their physical appearance: under-nourished and cheaply clothed, they presented a start contrast to the well-covered women of the upper ranks. They accentuated their distinctiveness by keeping together in one corner of the hall, well away from the congress promoters.? Their leader, Aleksandra Kollontai, would later achieve fame as the promoter of women?s issues within the Communist Party after the demise of the Provisional government of Kerensky (which had granted women the right to vote) and the Bolshevik takeover of Russia in October 1917.

During the 1908 congress, this women Workers? Group staged a deliberate walkout, over the question of whether women's suffrage should be restricted (according to property qualifications) or "universal." Then the sessions ground to an abrupt halt by Sof?ia Dekhtereva?s unscheduled speech against the death penalty ? referring to the numerous executions taking place at the time. Yet the congress had done its work and recorded its transactions ? a ?first? in the annals of Russian history.

Earlier this year, a group of Russian women?s historians organized a commemorative conference in St. Petersburg to honor this historic Russian ?women?s parliament? and to discuss new developments in Russian women?s history. Clio enthusiastically awaits the publication and rapid dissemination of their findings.

Source: Linda Edmondson, ?The First All-Russian Congress of Women,? in her book Feminism in Russia 1900-1917 (Stanford University Press, 1984), pp. 83-106. Quotations, pp. 104, 88.

Further reading: Encyclopedia of Russian Women?s Movements, ed. Norma C. Noonan & Carol Nechemias (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001); Barbara Alpern Engel, Women in Russia 1700-2000 (Cambridge University Press, 2001); Natalia Pushkareva, Women in Russian History: From the Tenth to the Twentieth Century (M. E. Sharp, 1997).

What did the Seneca Falls Convention?s Resolutions Call For?

2008-09-11 12:51:56.000

Here are the Seneca Falls Resolutions, 1848:

The following resolutions were discussed by Lucretia Mott, Thomas and Mary Ann McClintock, Amy Post, Catharine A. F. Stebbins, and others, and were adopted:

WHEREAS, The great precept of nature is conceded to be, that ?man shall pursue his own true and substantial happiness.? Blackstone in his Commentaries remarks, that this law of Nature being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding all over the globe, in all countries, and at all times; no human laws are of any validity if contrary to this, and such of them as are valid, derive all their force, and all their validity, and all their authority, mediately and immediately, from this original; therefore;

Resolved, That such laws as conflict, in any way, with the true and substantial happiness of woman, are contrary to the great precept of nature and of no validity, for this is ?superior in obligation to any other.?

Resolved, That all laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and therefore of no force or authority.

Resolved, That woman is man?s equal ? was intended to be so by the Creator, and the highest good of the race demands that she should be recognized as such.

Resolved, That the women of this country ought to be enlightened in regard to the laws under which they live, that they may no longer publish their degradation by declaring themselves satisfied with their present position, nor their ignorance by asserting that they have all the rights they want.

Resolved, That inasmuch as man, while claiming for himself intellectual superiority, does accord to woman moral superiority, it is preeminently his duty to encourage her to speak and teach, as she has an opportunity, in all religious assemblies.

Resolved, That the same amount of virtue, delicacy, and refinement of behavior that is required of woman in the social state, should also be required of man, and the same transgressions should be visited with equal severity on both man and woman.

Resolved, That the objection of indelicacy and impropriety, which is so often brought against woman when she addresses a public audience, comes with a very ill-grace from those who encourage, by their attendance, her appearance on the stage, in the concert, or in feats of the circus.

Resolved, That woman has too long rested satisfied in the circumscribed limits which corrupt customs and a perverted application of the Scriptures have marked out for her, and that it is time she should move in the enlarged sphere which her great Creator has assigned her.

Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.

Resolved, That the equality of human rights results necessarily from the fact of the identity of the race in capabilities and responsibilities.

Resolved, therefore, That, Being invested by the Creator with the same capabilities, and the same consciousness of responsibility for their exercise, it is demonstrably the right and duty of woman, equally with man, to promote every righteous cause by every righteous means; and especially in regard to the great subjects of morals and religion, it is self-evidently her right to participate with her brother in teaching them, both in private and in public, by writing and by speaking, by any instrumentalities proper to be used, and in any assemblies proper to be held; and this being a self-evident truth growing out of the divinely implanted principles of human nature, any custom or authority adverse to it, whether modern or wearing the hoary sanction of antiquity, is to be regarded as a self-evident falsehood, and at war with mankind.

At the last session Lucretia Mott offered and spoke to the following resolution:

Resolved, That the speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women, for the overthrow of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for the securing to woman an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions, and commerce.

Source: ?Declaration of Sentiments? and ?Resolutions? adopted by the Seneca Falls Convention of July 1848; from History of Woman Suffrage, ed. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, vol. 1 (New York, 1881), pp. 70-73.

Visit the website of the Women?s Rights National Historical Park, in Seneca Falls and Waterloo, New York, USA. www.nps.gov/wori

from Google Images

Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony, statue in the U.S. Capitol Building

from Google Images

Women's Rights National Historical Park commemorative pin

Clio Revisits the Declaration of Sentiments, Seneca Falls, July 1848

2008-09-09 17:09:31.000

Just 160 years ago an extraordinary event took place in Seneca Falls, a small town in upstate New York, in mid-July 1848. A little band of women, mostly Quakers, who had been active in the antislavery movement, called a convention to discuss women?s rights (or lack of rights) in the United States. Several hundred persons, including both women and men, came to this convention and voted on the Declaration of Sentiments.

Paraphrasing the American ?Declaration of Independence? (1776), the Declaration of Sentiments also established a list of resolutions, including a demand for women?s right to vote. The press reaction was strongly unfavorable to the conention's demands, but the message of this Declaration echoed throughout the country and around the world.

A second convention took place in Rochester, New York, just a few weeks later. A number of other conventions followed, and gave birth to the movement for women?s rights in the U.S.

Here is the text of the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments:

DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS

Seneca Falls, New York, July 19-20 1848

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves, by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men -- both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master -- the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women -- the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education -- all colleges being closed against her.

He allows her in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public particiation in the affairs of the Church.

He has created a false public sentiment, by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, -- in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

Firmly relying upon the final triumph of the Right and the True, we do this day affix our signatures to this declaration.

Clio will provide the Convention?s resolutions in her next blog.

Why Did Chinese Women join the Red Army?

2008-09-03 17:10:13.000

Clio is fascinated by women who have joined revolutionary movements. Some, of course, sign up because they believe strongly in the principles of the movements. Others joined, as Helen Praeger Young?s interviews with twenty-two Chinese women who went over to the Red Army and participated in the 6000-mile Long March (1934-1936), because they had little to lose, because they were hungry and the army would feed them, because they wished to escape from servitude and abuse, because they sought literacy and further education. These women recognized, not only in retrospect, that the condition of women in Chinese society ? even after the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty in 1911 ? left much to be desired. The situation was especially grim for girls and women in the countryside.

Some might have heard that in the 1920s the Communist International had embarked on a campaign to recruit women. In November 1931 the First Congress of the Chinese Soviet Republic had drafted a Provisional Constitution that specifically addressed women?s emancipation as a goal:

?It is the purpose of the Soviet government of China to guarantee the thorough emancipation of women; it recognizes freedom of marriage and will put into operation various measures for the protection of women, to enable women gradually to attain the material basis required for their emancipation from the bondage of domestic work, and to give them the possibility of participating in the social, economic, political and cultural life of the entire society.?

But as China expert Helen Young discovered, others, hearing that the Red Army, headed by Mao Zedong, had reached their region, clamored aboard for more personal reasons. One woman recounted her family situation thus: ?My own mother had twelve children: four dead, eight living. The three of us girls were sold, leaving five. Four of my brothers were sold abroad in Southeast Asia. Finally, there was only one younger brother left. In the old society, we called it ?selling baby pigs.? There was no alternative. You bore one child, gave it away, and bore another.? Another responded: ?Why did I join the army? To go find food to eat. There was no food at home.? A third also indicated that ?There was no food at home. When you join the army, you have food to eat and clothes to wear.? In sum, these women ? who were very young at the time ? really had nothing to lose. They were more adventurous than those that stayed behind.

Young summarizes the situation this way: ?The urgency that impelled the women to join the revolution rose directly from their being women. They expected even greater changes in the way they would live their lives than the men did. . . . As part of the communist revolution, they were no longer just the property of the men in their families; they demonstrated their independence by cutting their hair and thus cutting the symbol of marital status. The army paid off the families they ran away from, sheltered them from abusive families, gave them jobs that took them outside the prescribed confines of their homes, and taught them to read and write. The appeal of belonging to the revolution was powerful to a woman who had been sold into child servitude, prevented from going to school, or physically abused, and offered her a way to avoid being married into a strange family, or living the half-life of an unmarried servant in her ?in-law? family. . . . The revolution drew them into an exciting new life, a safer and more interesting place in society, and granted them a sense of belonging and a patriotic purpose.?

Source: Helen Praeger Young, ?Why We Joined the Revolution: Voices of Chinese Women Soldiers,? in Women and War in the Twentieth Century, ed. Nicole Dombrowski (New York: Garland, 1999), pp. 92-111.

See also: Helen Praeger Young, Choosing Revolution: Chinese Women Soldiers on the Long March (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001).