Digital Livelihoods for the World's Women

Digital Livelihoods For the World's Women

How One Company is Proving that Work for Women Matters

One of the reasons women are undervalued globally is the lack of opportunities that allow women to use their brains (rather than their bodies) to earn income, says Samasource CEO Leila Chirayath Janah. But Samasource is spreading digital work to women in the poorest parts of the world, providing themwith training, internet access and a cheap laptop, and giving them skills that will help bring them out of poverty. Through their efforts to spread digital work to women in developing countries, Samasource hopes to create sustainable economic opportunities for women, and prove that work for women matters.

Why Are Women Undervalued?Sixty million women around the world, largely in developing countries, have gone missing. They are selectively aborted, denied basic medical care, married off early (resulting in a higher risk of maternal mortality), forced into prostitution, and, in some cases, killed to preserve their families' honor. This "gendercide," argues Pulitzer Prize-winning author Nicolas Kristof, is the great moral scourge of this century, akin to slavery.

I am generally disinclined to trust bold statistics unless they're cited by people with experience in analyzing data -- it's easy to manipulate numbers into telling whatever story one wants to hear. So it's worth noting that the figure above comes from none other than Harvard economist Amartya Sen, who examined this issue in the early 1990s. In fact, Sen found that the number of missing women may be closer to 100 million, when you account for women's longer life expectancy and all the ways women are mistreated: an estimated 2 million girls starve because their parents don't feed them as much as they feed boys; 3 million are forced into trafficking and prostitution; and in India, millions of young girls perish as a result of poor health care -- they're 50% more likely than boys to die between the ages of one and five.

Why are women so undervalued compared to men?

I've heard many explanations, ranging from culture and religion to evolutionary biology. But none seem quite as salient as this one: women are less valued by society because they earn less money than men do.

I'm not talking about wage differentials in the developed world (though it's frustrating that women still earn 85 cents for every dollar a man earns, globally). I'm talking about a dramatic lack of access to opportunities that allow women to use their brains, rather than their bodies, to earn income.

Providing Work for WomenAs literacy rates rise and more women are prepared to enter the formal labor force, fewer and fewer jobs are available to them. We've seen a tremendous surge in human capacity -- 84% of the world can now read and write. Even in poor countries, just as many women are graduating from universities as men, and the proportion of women in college is increasing, according to the UN.

But there has not been a parallel surge in economic opportunity, particularly for women. Globally, the sex ratio among adults is around 1.01 males for every female. If economic opportunity were distributed equally, we'd expect no more than a percentage point difference between male and female employment rates. Instead, the difference is closer to 20% -- the ILO reports that women make up roughly 1.2 billion of the 3 billion employed people around the world.

Those women that are employed often work for poverty-level wages, in what is called "vulnerable employment" -- jobs that don't provide any security and are not likely to build a woman's skills, such as low-level manufacturing work in export processing zones. In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, a whopping 80% of women workers are in vulnerable employment, according to UNIFEM. The financial crisis has exacerbated this problem: in Ahmedabad, India, for example, garment sector workers' monthly earnings have dropped by 50% and days of work by 69% since November 2008. Across all of India, 700,000 clothing and textile workers lost their jobs in 2008. With factories closing down and production moving to other locations, women are forced to take multiple low-income jobs while keeping up their unpaid commitments to care for their families.

So even women who are lucky enough to find a job after college are forced to work in low-wage sectors that keep them in poverty or expose them to terrible working conditions. During our field work in Nairobi, Kenya, I met a young woman named Freda Adundo, from a rural part of the country. Freda is a bright young woman who'd worked her way up through the Kenyan education system and was about to receive an IT degree. She told me, "the dilemma in Kenya, and Africa at large, is that the cost of education is getting so high that upon finishing, you can't get a job that will offer returns commensurate with what you've done in school." Freda was right--the average Kenyan family spends 277% of per-capita income on tertiary education.

Our focus in the development community must not only include educating women, but also connecting them to jobs that tap these newly-formed skills.

Digital Work: A New Kind of LaborLuckily, there's a new kind of work out there, and unlike manufacturing, it requires few inputs. You don't need roads, or telephone lines, or brick and mortar to build this generation's factories.

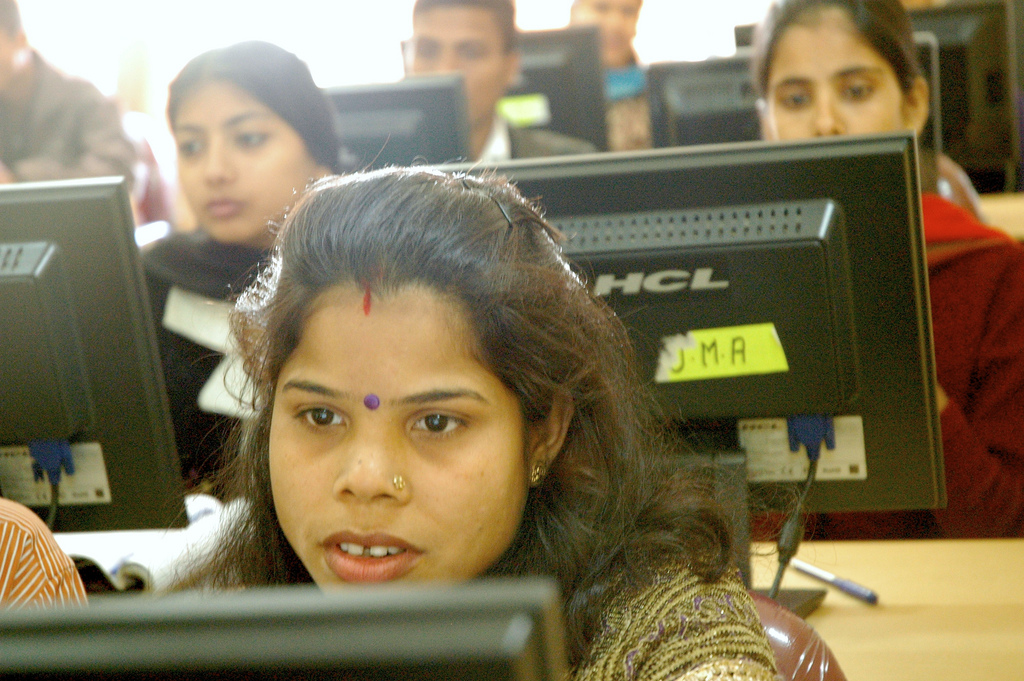

All you need is a brain and a cheap laptop connected to the internet. The primary input of this new digital work is human intelligence, which we now have in abundance. A few years ago, Tom Friedman wrote a book called The World is Flat, which described how the $200 billion global outsourcing industry was creating a new middle class in India and China through the creation of information technology jobs. Now, it's not just IT jobs that the internet enables. Any work that can be done digitally, from labeling an image to translating a snippet of text, is now fair game. This is creating a rapid transformation in the types of people that can do digital work. Just as Ford's assembly line took production into the mainstream and paved the way for the rise of the American middle class, the digital assembly lines of today allow people with basic training to plug their skills into much larger work streams that engage hundreds of people on many continents. The Internet is the new factory floor.

Samasource takes this new digital work and plugs in a new kind of worker--marginalized women, youth, and refugees living in poverty--creating a value chain that pumps much-needed capital into some of the poorest parts of the world.

Digital work can be hard to grasp, so let me provide an example. In February last year, while I was traveling in Pakistan on the hunt for new partners, a woman named Maria Umar emailed me. She mentioned that she had heard we were training people to do work over the Internet, and explained that she was a mother of two in a place called Rawalpindi and had just lost her job as a teacher. Maria, I discovered, had a Master's Degree in English and was making less than $100 a month teaching -- not enough to pay her children's expenses. I interviewed Maria over Skype and decided we'd take her on and train her to do administrative work, something few of our other partners could handle. Within a few months, Maria was up to speed and had her first customer, a project manager at the Young President's Organization who needed help managing her calendar and transcribing notes. We worked with her to form a company, the Women's Digital League, that now employs twenty-two young Pakistani women in similar work. Each of them earn at least double what Maria made as a teacher, in under half the time.

"I'm earning more than most of the men in my village thanks to Samasource, and I'm helping other women in my position work from home," says Maria. "And they are slowly, gradually, getting the idea that they don't have to be helpless victims sitting at home...Samasource has given me a sense of self esteem that I've haven't had in the last 30 years."

Why Work for Women MattersIn the last year, with a modest initial investment and a ton of sweat equity, Samasource has grown to serve hundreds of women across Africa, South Asia, Haiti, and partnered with several companies in Silicon Valley as sources of work, including Intuit, Google, GoodGuide, and Benetech. The income that enters the system from these jobs has a multiplier effect -- by training marginalized women in digital work, we not only provide direct employment, but we also increase household spending on health and education, increase a woman's wages substantially over her lifetime, and decrease the likelihood that she will be forced to leave her community to find work. There is much evidence that providing dignified work to women also reduces the chances that that they will be victims of violence, trafficking, or suffer exploitation in the workplace.

Work for women matters, and this message is finally getting through to global leaders in major development institutions. Investing in women's livelihoods, and connecting them to digital jobs in the new economy, can pave the way for sustainable growth and development in the poorest parts of the world.

For women like Maria, dignified work means more than mere income -- it's a new identity, beyond being someone's wife or daughter. "The men in my village and even in my family tell me that they are willing to respect me now."

By investing in and spreading the word about digital work that promotes women's employment, we have the power to unlock a vast and untapped pool of talent. The women of the world are waiting.

To learn more about Samasource's work, visit www.samasource.org.

References:

-

Gains and Gaps: A Look at the World's Women. The National Council for Research on Women. March 2006. New York, New York.