Kashmir and Elections

Featured Community Voice: Ather Zia

Kashmiri scholar, journalist and former civil servant Ather Zia offers a detailed and rarely discussed history of the elections and campaigns in the disputed region of Kashmir in India. She explains the complicated history of the region and delves into the serious issues regarding Kashmiris' general disenchantment with electoral politics, women's near invisibility in leadership positions, women's political kinships, rigging, and the Kashmiri struggle for self-determination.

A Saga of Ambiguity and Disenchantment

Kashmir and elections share a tense and confusing history. It is a history where some men take to opportunist politics, some are reluctant to participate, some steer clear while women, ironically, become visible through their near-absence. The polity in Kashmir is a peculiar species and what may be seen as a democratic value elsewhere does not translate the same way for the people of this conflict-ridden region. Hence, elections--universally seen as democracy in action--do not mean the same in Kashmir.

In order to understand women's involvement--rather, non-involvement--in Kashmiri elections and campaigns, it is important to take a look at the history of Kashmir's tumult. It is important to understand that the lopsided gender engagement in Kashmiri politics is not indicative of women's political illiteracy, but a result of a turbulent political environment borne by Kashmir's disputed alliance with India and the armed struggle.

Ever since India and Pakistan became free from Britain they have fought over the territorial domination of Kashmir.

Since 1948, Kashmir has been divided in two, with far northern and western areas controlled by Pakistan and the rest by India. According to the U.N. resolutions, a plebiscite is supposed to determine the country's final status. India, however, disagrees and argues that elections held in Indian-occupied Kashmir annul the need for plebiscite. As a result, the electoral politics in Kashmir are today fraught by conflicting debate and restiveness.

The Runnel of Rigging: Whatever Floats Your Boat?

In this quagmire of dubious polity, Kashmiri people, no doubt politically aware, are disenchanted with politics. In a scenario where men are wary of joining politics, it's no surprise that politics have not been a priority for women, who are otherwise increasingly active as professionals and productive members of the society. The process of elections in Kashmir has historically entailed rigging and suppression of dissent, which even well-known Indians have criticized.

Tavleen Singh, a reputed Indian journalist, uses the term "rigged elections and sham democracy" to describe Kashmir polity. As reported by the BBC in 1996, Indian Home Minister Inderjit Gupta, said ". . . in Jammu and Kashmir all elections held to date were rigged to serve the interests of successive Congress governments." An uninterrupted history of rigging has even been acknowledged by the right-wing hardliners like L. K. Advani, the former prime minister of India.

In 1986, the political discontent led to a formation of a new party, Muslim United Front (MUF), which had the support of pro-independence activists and other disenchanted Kashmiris. For the first time since partition of Independent Kashmir, groups adverse to Indian administration tried to seek a solution through a mainstream political process.

However, the elections were rigged once again, this time by the ruling National Conference (NC) party, and the MUF leaders and supporters were arrested. This event proved to be a watershed moment, followed by an armed uprising that began a new chapter of Kashmir conflict.

In 1996 elections, held after a decade of electoral silence, even Farooq Abdullah, head of the National Conference and the chief minister in 1987, went on record to call the elections "farcical and rigged."

Most of the elections since then have been held under the control of armed forces and other government wings and have been boycotted by the majority of Kashmiris.

Cosmetic Democracy & Election Woes

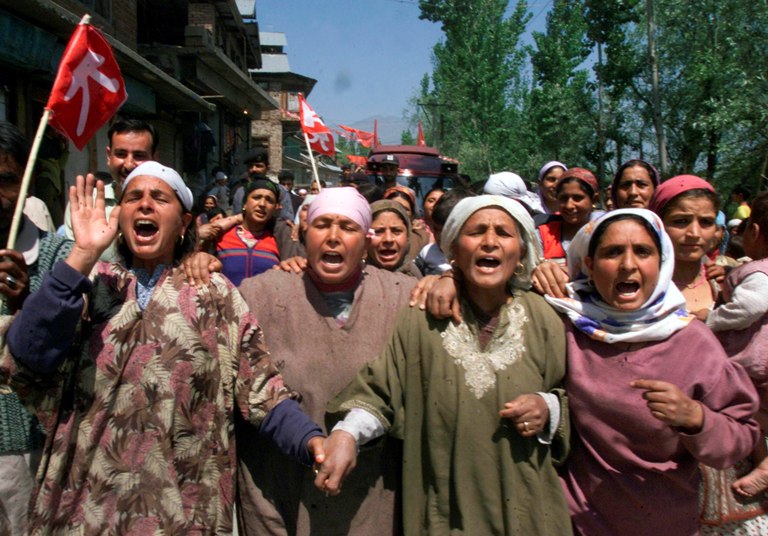

The process of elections and campaigning has a different mood in Kashmir. Candidates contesting elections usually function under maximum security. Although there may be token banners and placards announcing candidates, the routine fanfare accompanying such events is missing as is the attendance of mainstream masses.

Rallies often take place in rural areas where unlettered populations living in adverse and ignorant conditions may attend. Canvassing in urban areas is almost non-existent. Most people do not even know who their district representatives are.

Considering the situation, establishing regular elections and forming an elected government is not a solution to ensuring a true democracy in Kashmir. In 2002, the Crisis Group reported: "If the Indian government chooses to act as if the elections alone were sufficient to address a myriad of Kashmiri grievances, it will only be a matter of time before violence again escalates--just as it did in the run-up to the ballot itself."

Elections in Kashmir ensure the continuity of a political engagement with India which bears a democratic patina, but essentially thwarts the efforts for addressing the demand for self-determination. In spite of unabated elections, the Kashmir conflict remains alive.

Women & Political Non-Participation

With a political process that not only has a shaky foundation but also lacks popular support, it's no surprise that Kashmiri women have rarely joined politics. Although there are a handful of women practicing politics, their emergence can easily be traced back to dynastic influences.

When the 87-member Assembly was dissolved, only one woman, Sakina Itoo of the National Conference (NC) party, was elected. She was studying to be a doctor when her father was assassinated. After his death, she inherited his position. Besides her, two other women were nominated by the NC, which has yet to announce its quota for women. The NC, however, recently installed Shamima Firdous as the head of a newly formed women's wing.

Currently the only female face in Kashmiri politics is the pro-India Mehbooba Mufti, who fielded three women candidates from her party, including herself, in the last election. Ms. Mufti's foray into politics and her subsequent rise in pro-Indian politics can be attributed to her prominent politician father. In an interview with Business Line, Ms Mufti talks about the difficulty of finding women candidates:

"I would love to have as many women candidates as possible, because I do believe that thanks to their gender, women politicians are better equipped to empathize with the people of Jammu and Kashmir, who have undergone a lot of suffering and have had to give a lot of sacrifices. But in a situation where it is difficult to find even good men to come forward and contest--they demand security which we can hardly promise--it is a little too much to expect women to rise above their role in such a traumatized society and come forward to participate in the political process."

The few women visible on the Kashmiri political firmament since 1948 all owed their participation to family affiliations. Begam Jehan, the wife of Sheikh Abdullah's, leader of National Conference and mother of Farooq Abdullah, was a social activist and a member of the Indian parliament. There were some other women in her coterie as well.

Zainab Ji came from a political family and was an activist, as was Mahmuda Ali Shah, a progressive leftist. There have been women like Zoona, a milkmaid by profession, who was an active member of the Quit Kashmir Movement of 1946. Krishna Mishri from the Hindu-Pandit community spearheaded the teacher's movement.

Separatist Politics and Women

The only prominent female face in the separatist struggle is the orthodox hardliner Asiya Andrabi who is active in her organization Dukhtaran-i-Millat (Daughters of the Community). After the recent protests against India, police confirmed that Asiya has been booked under the Public Safety Act, under which can mean imprisonment for up to two years without trial. A few women's separatist groups like the Muslim Khawateen Markaz and the Kashmir Women's Forum are also active.

Today, the number of Kashmiri women joining the area of arts and literature, law, journalism, administration and entrepreneurship is increasing. Nevertheless, the process of politics does not hold much attraction for them given the overarching role that separatism holds in the Kashmiri state of affairs and the immense number of lives lost for the cause.

Even though the state is being hurled into another election later this year, there is no fervor among people. Presently, a strong grassroots movement has emerged that eschews armed resistance and pursues a non-violent struggle for self-determination. Armed groups have announced a ceasefire, paving the way for a peaceful resistance marked by mass protests, vigils, rallies and prayer congregations. Kashmiri women are proving to be keen supporters in this emerging political environment.

To read more about my work on Kashmir, visit my online magazine KashmirLit. Submit work for the next issue.