A Struggle within a Struggle

Comandanta Esther of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation Speaks Out

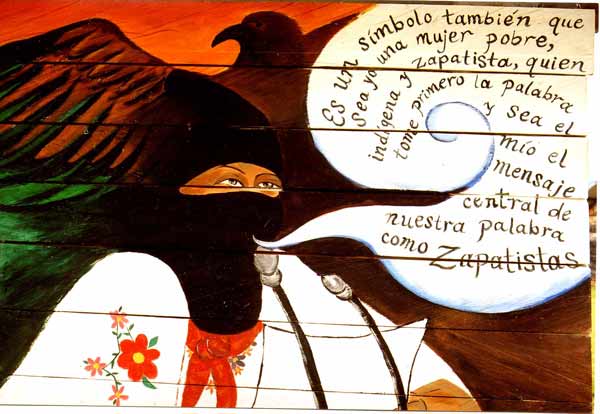

Women hold a record number of powerful positions in Mexico's Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). One such high-ranking woman is Comandanta Esther, seen to the left in a mural painting. Like all those involved in the Zapatista struggle, she obscures her face with a mask.

The Zapatistas take their name from Emiliano Zapata, a leader of Mexico's 1910 revolution. Based in the southern, farming state of Chiapas, their cause is to control the land on which they live, and preserve their traditional, indigenous way of life.

On March 8, 2001, on International Women's Day, Comandanta Esther issued an invitation to women across Mexico to join in the struggle. The voices and experiences of Zapatista women are heard through the words of Comandanta Esther.

When I was a little girl I was hungry and sick. Even though we didn't eat well, here we are. We go on.

I didn't know how to speak in Spanish. I went to school, but I didn't learn anything there. But when I entered the organization (EZLN) I learned to write and to speak Spanish, the little bit that I know. I'm engaged in the struggle.

Once I grew up I began to see that we didn't have adequate food, that others did and we didn't. Why didn't we? I saw that I had four or five little brothers and sisters who had died, that's when I realized: ‘Why were my little brothers and sisters dying?' I saw that it was necessary to fight, because if I didn't do anything other brothers would keep on dying, and I decided. And not only me, there are women who decided to be soldiers, and those women now have the insurgent rank of Captain, of Major, of Lieutenant. That's how we saw that women can indeed be strong.

In the beginning, I had to pay a price for the truth. The men didn't understand, even though I always explained to them that it was necessary to fight so that we wouldn't always be dying of hunger. The men didn't like the idea. According to them, women were only good for having children, and they should take care of them.

And there are also some women who have that idea in their heads. Then I didn't like them. Some men said it wasn't good, that women didn't have the right to participate, that women are stupid. Some compañeras said, 'I'm stupid.' I always confronted that. I explained to them that it wasn't true, that we are women, but we can do other work. Little by little the men began to understand, and the women also. That's why women are fighting now. That's why you know that in our fight it's not just the men who are fighting here, we're fighting together.

Since the war began, the bad government has been putting the armies in, but the ones who have had to confront that problem are the women. The militarization has been very hard, but the women haven't been afraid. They've gone out to run the soldiers off. And so we've seen that women do have strength, not with weapons, but with strength and with shouts. We see that as women we can be strong.

The truth is that we have resisted, even though it has been years since the war began. Despite the suffering, we are still here. If we hadn't resisted, we wouldn't still be here. Though a lot has happened to us, in spite of that, we haven't surrendered. We've been strong.

As Zapatista women we've made a little progress. We saw that we didn't have anything, and we asked ourselves, ‘Who is going to give us anything if we don't do anything?' We ourselves have to work, to help each other in order to have the little we need. The women began working in collectives, then, in bakeries, vegetable gardens, and other things.

Before, women didn't participate in meetings, in the assembly, because their husbands wouldn't let them. The men understand now; women can go to meetings, and men can stay at home taking care of the animals. Now if men see that there's a lot of work in the kitchen they help their wives or theircompañeras. They didn't do it before. Now they do. There's change.

We ourselves explain to the boys and girls that there should be respect, that we are equal. The girls and boys go to school. And not just them, but the older women as well, because they learn well there. The men go also. Because we ourselves are organizing now, and we're not in the government schools anymore but in our own autonomous educational system. We all go there.

I believe we're going to achieve the change we want if it's going to be achieved, because I see many women organizing themselves. We invite them also, and that way we'll have more strength. We're going to achieve it, with all of us."

Excerpted from a speech originally printed in Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas edited by Shannon Speed, R. Aίda Hernández Castillo, and Lynn M. Stephen and published by University of Texas Press: Austin, copyright 2006.