Théâtre Aquarium

Watching Real Life in a Fishbowl

My interpreter, Scheherazade Matallah, and I climb the steps to Naima Zitan's apartment, one room of which doubles as an office for Théâtre Aquarium. Three senior members of the organization lean on the table and passionately describe their history and dreams in a cacophony of French and Arabic. They switch from one language to another mid-sentence and everyone laughs as Scheherazade, undeterred, translates the jumble into English for me.

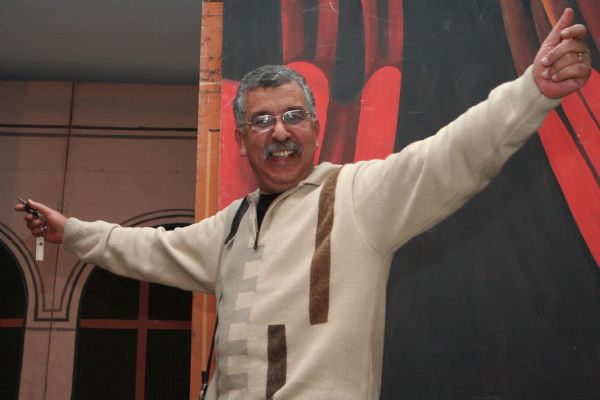

Watching real life through a fishbowl, these images depict productions from Théâtre Aquarium

"Abdullatif was working in women's associations?" I marvel.

"Yes! I am 100 percent feminist" he nods.

"If he weren't, he wouldn't be working with us!" his sister laughs.

Naima Zitan continues. "In 2000, we collaborated with a nongovernmental organization, Jossour, to defend the National Action Plan. Our play was called Stories of Women. We performed in front of thousands of associations. The opposition demonstrated against us. During this time, we learned that 60 percent of Moroccan women are illiterate. We were shocked and decided to take our performances to them. Between 2000 and 2002, we performed Stories of Women 50 times, in rural areas, souks, markets, and mosques. The Moudawana reform is, in part, a result of our activism," she acknowledges without hubris.

"The amendment of the Family Code was extraordinary," Zitan observes. But few illiterate people knew about the new Moudawana and even fewer understood it. "In 2004, we created a new play, Coquelicot, to explain the new law."

Abdullatif jumps from his chair and beckons me to the computer, where he has mapped a welter of national literacy data. "We had to work hard to collect this information," he admits, "since the government wanted the statistics to be confidential. In these areas," he says pointing to red districts on the screen, "more than 85 percent of the population is illiterate. That is where we take our performances: to prisons, hospitals, factories, orphanages, and, of course, theaters."

"Our mission is to explain to women what their rights are now. It's not easy for people to change after so many years, but if they don't understand, they cannot demand their rights and the new law is useless," says the visionary Naima Z, who is president and artistic director.

"Before every performance, we ask what people in the audience know about the new Family Code. Usually they give us wrong information and wrong definitions. After the play, we ask them what they learned and what was clarified. For us, it's a technique to evaluate the effectiveness of the presentation. This part is my job because I talk the most," laughs Naima O., whose title is public relations director.

One early afternoon, the two Naimas, Abdullatif, Mbarka El Ouazzani from Jossour, Scheherazade, and I jam into a compact car and head for the suburb of Temara. Naima Z. has been working at her job at the Ministry of Culture, and, in need of a power nap, falls asleep en route.

Naima O. tells me, "Naima and I met when I was working with Jossour, and we decided to try social theater. She is 38, a Berber from the North, and artist. I am 42, an Arab girl from the South, an archeologist. We both have regular jobs, and work for Théâtre Aquarium out of love." The two appear to be opposites: introvert and extrovert; Zitan chain smokes three packs a day, Oulmakki doesn't smoke; Zitan drinks water at lunch, Oulmakki quaffs a glass of beer. "But we care about the same deep existential questions: why, when, where? In that way, we are exactly the same."