Women's Justice

Originally established in 1994 by the non-profit organization Action India, Mahila Panchayats are voluntary women's courts that settle disputes between individuals.

At first impression, the Mahila Panchayats do not appear to have the legal teeth needed to bring justice: The accused parties do not have to show up when summoned, and the women members have few ways of enforcing their decisions. But time and again, their courage and persistence have proven to move their communities closer to justice.

"Mahila" means woman in Hindi, whereas "panchayat" literally stands for an assembly(yat) of five (panch) respected village elders. Panchayats already exist in India. Every Indian village has its own panchayat that governs that particular village. Mahila Panchayats are an all women's grassroots variation on that governmental body that gives women an opportunity and space to seek redress for their private injustices--mainly domestic violence and sexual harassment.

And although they are voluntary, experience has shown that both men and women respond to their calls, and heed their decisions. Only last year, the thirty eight Mahila Panchayats across India have resolved 1,800 cases of domestic violence. Even local policemen have started referring cases to them.

The main reason for Mahila Panchayats' success is their use of social pressure to their advantage. Mahila Panchayats use the power and influence of community to publicly shame people into appearing and complying with their final judgments. People who decide to ignore their decisions face possible embarrassment and ostracism.

The Mahila Panchayats comprise of women panchayat members and two women paralegals trained by Action India. The paralegals are trained in women's rights, gender-based violence and in the ways of effectively holding hearings, following up on their cases and working with the police.

The paralegals organize a Mahila Panchayat by first building relationships with the community and identifying female members in that community that could strengthen, with their authority and personality, the panchayat. Once an assembly is created, cases begin to be heard. Mahila Panchayat cases across India are heard on Wednesdays of every week. After the first hearing, a notice is served calling the other party to the panchayat. Both parties are then encouraged to speak face-to-face and resolve conflict on their own terms. A compromise and, in some cases, settlement are written on an official letterhead paper in the presence of witnesses.

Once a case has been concluded, follow-up is crucial. The paralegals visits the family in question as many times as necessary to determine that the family is upholding its responsibility to the compromise made in the panchayat.

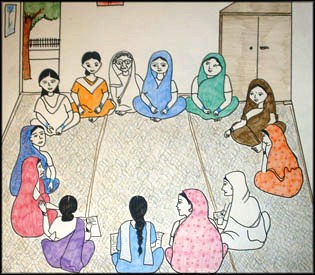

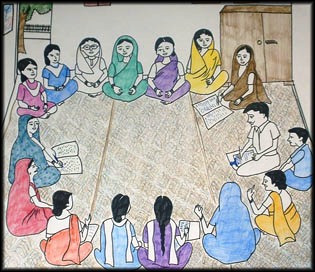

What follows are summaries of two successful Mahila Panchayat cases that dealt with sexual harassment and domestic violence. The hand-drawn representations of one Mahila Panchayat case depicts the Indian women's collective power in making their voices heard and resolving domestic violence. The images show how women, staging a public hearing and baring their proverbial "dirty laundry" to the public are challenging face-to-face their husbands and other men and making their rights known. The images also show the power of women'scollective bodies and wills in intimidating and forcing men to comply. In the fifth image you can see four Mahila Panchayat women surrounding a single man and convincing him, with their sheer numbers and determination, of his wrongdoings.

Case: Sexual Harassment

Plaintiff: Geeta Rani

Sixteen-year-old Geeta Rani was constantly followed and pursued by her neighbor Niranjan. She could not step out of her home (in an urban slum in Delhi) without the young man taunting her: He hooted, whistled and teased her relentlessly. Geeta had the courage to lodge a complaint at the local police station. The policemen arrested Niranjan, beat him up and warned him against harassing Geeta. Twenty-four hours later, he was released and was back to his usual "eave teasing" (street/ public sexual harassment).

Afraid for her safety (there are incidences in India where rejected admirers revenged themselves by throwing acid in the face of women/girls), Geeta Rani sought help from the Mahila Panchayat. After hearing her story, they registered her complaint. The members and paralegal workers enquired around and questioned Geeta's neighbors who confirmed the boy's offensive behavior. They sent a notice on their letterhead to Niranjan asking him to appear before the Mahila Panchayat next Wednesday.

It took two hearings to resolve the case. During the first hearing, Niranjan appeared with his mother. He denied all charges and the case was not resolved. During the second hearing, a long discussion with the boy opened doors for counseling. Niranjan acknowledged his mistakes and agreed not to bother Geeta again. The Mahila Panchayat members asked him to give his word in writing, but he refused to do so. As a result, Mahila Panchayat members lodged a complaint at the local police station seeking protection for Geeta in order to pre-empt any future incident.

Follow-up by the Mahila Panchayat members was successful. They found that Geeta was happy and free to move out of her home without being followed or teased. Geeta has since become an active member of the Mahila Panchayat. She has shown great courage in voicing her protest in doing so she has asserted her right to live free of fear of violence and live life with dignity.

Case: Domestic Violence

Plaintiff: Munesh

Munesh came to the Mahila Panchayat office in her community in an urban slum in Delhi. She lodged a complaint against her husband Kanwarpal who was unemployed and refused to work and support his family of four. He would come home drunk and quarrel with Munesh every day. Often, he would get physically violent. He was also very possessive and controlled Munesh's every move. He refused to allow his wife to get a job and earn money to feed her children.

After Munesh logged a complaint with the Mahila Panchayat, the members and a paralegal worker visited Munesh's home to witness first-hand the situation. They found the husband at home and persuaded him to allow Munesh to get a job as a domestic worker as well as to make an effort to find work himself. Faced with so many determined women in his own home, Kanwar Pal realized he could not beat up his wife to vent his frustrations. After a few counseling sessions he stopped abusing his wife.

Follow-up by the Mahila Panchayat was successful. They found out that both Munesh and Kanwarpal have started working and together were managing to provide for their children.