Emancipated Woman – Build Up Socialism!

Propaganda Posters in Communist Russia

In 1923, the American Journalist Albert Rhys Williams noted a ubiquitous feature of the Russian urban landscape: the poster. "The visitor to Russia," he wrote, "is struck by the multitudes of posters--in factories and barracks, on walls and rail-way cars, on telegraph poles--everywhere."

Indeed, there were over 3.2 million posters distributed in 1920 alone by Gosizdat, the state publishing house and 7.5 million during the following three years. A Russian woman living in the 1920s and 1930s would have met images of herself--or how she was supposed to be--on almost every street corner. What purpose did this mass propaganda serve? What do these posters tell us about the changing role of the Soviet woman?

At first, few Russian political posters featured women. Those that portrayed female figures did so allegorically: women were used to represent abstract ideas such as freedom or liberty. In 1918, after women were emancipated in the communist revolution, posters had more realistic representations: women depicted as workers and purveyors of socialist thought.

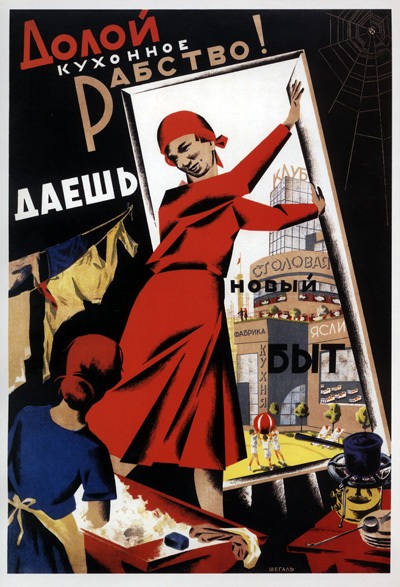

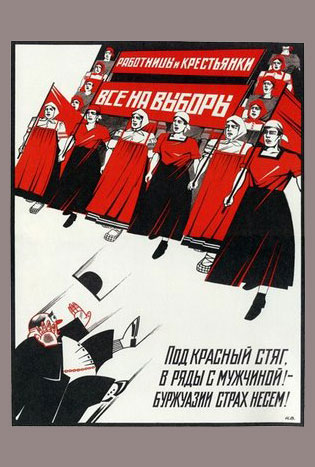

Communist propaganda posters also made use of vibrant colors--particularly red--which would have been instantly recognized as a powerful color in both communist and religious iconography. Women were portrayed wearing red headscarves -- tied in the back, in accordance with modern fashion. Or wearing red dresses, symbolizing their heroic stature under communism.

Political art of this time emphasizes women's productive rather than reproductive roles in the economy. Under the new Soviet constitution, women were granted the same civil, legal, and electoral rights as men--and they were expected to make equal contributions to socialism. Thus, day nurseries, kindergartens, and large-scale canteens were built to free women from domestic duties so they could work in factories and on collectivized farms.

Posters disseminated new visual scripts which liberated Soviet women were supposed to follow. Women were depicted riding tractors, for example, signifying progress. In reality, there were few women tractor drivers. But the message was clear: women were vital in the effort to modernize and collectivize agriculture.

Other posters contrasted women's lives before and after socialism. Political art beckoned women to step up and take advantage of new opportunities: to become literate, receive an education, vote, and, of course, fight the enemies of communism--capitalists and land owners. No longer did women need be confined to the home, exhausted by domestic labor.

Russian posters of the 1920s and the 1930s often portrayed women as larger-than-life figures, reflecting their new power and importance. But we must not forget that political propaganda is prescriptive as well as descriptive: it both reflects women's changing roles and provides them with a road map to a socialist future -- one that will only be successful with their contributions.