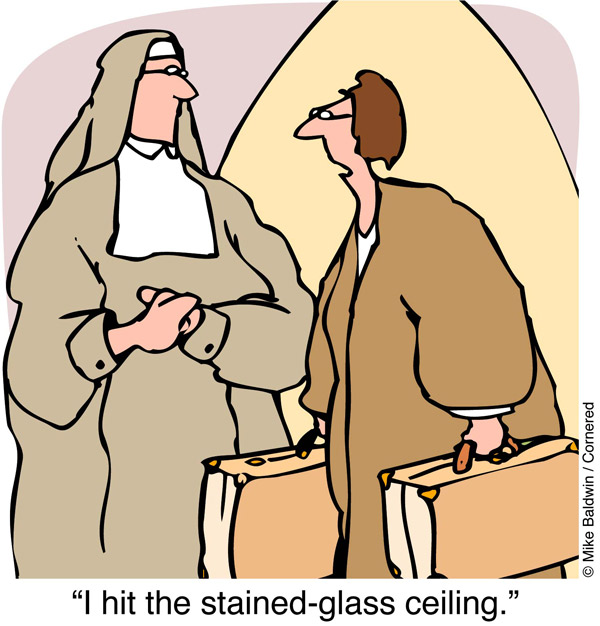

Does Religion Instigate Or Hinder Women’s Political Participation?

Curator Masum Momaya Introduces “Religion”

A review of history shows that "God" has been a dominant factor in whether or not women participate in politics. Separation of church and state is a myth in many countries in the world, and, in the minds and hearts of many, an undesirable goal. In some places, devotion and faith catalyze women to take up a cause, political or otherwise. In other places, the "powers that be" invoke interpretations of holy books to prohibit women's political participation - and relegate women to their homes and household duties. So, does religion ultimately instigate or hinder women's political participation?

In the 19th century, United States' anti-slavery activist Sojourner Truth exclaimed "If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, women together ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again." Her words convey one of many examples in which women have invoked their faith as a source of strength and meaning in their struggles for a more just world.

Burmese activist Aung San Suu Kyi once said, "I was born a Buddhist and brought up a Buddhist, so it is very difficult for me to separate what is Buddhist in me from what is not Buddhist in me."

If fact, clergy in some spiritual traditions have argued that women, because of their biological and social roles as mothers and caretakers, are particularly suited to bring about peace in the world. For instance, in 1930s Spain, the Catholic church open doors for fascist women of the Seccion Femenina de la Falange Espanola to fight publicly for social justice.

Today, Buddhist nuns and lay women in Sri Lanka and Nepal, Hindu women in India, Evangelican women in United States and Africa, Catholic congregation members in Latin America and Muslim and Jewish women throughout the Middle East all demonstrate that faith and activism can not only co-exist but co-inspire - some to the point of violence, others to the point of interfaith collaboration.

This invocation of religion, though, has proved to be a double-edged sword for women. While many communities have fought long and hard for the infusion of religious doctrine into legal codes, women now bear the burden of overturning increasingly prescriptive and restrictive gender norms that have been codified as law. This includes some form of the Family Code, which is present throughout the Arab world.

Invocation of religion has also brought along prescriptions for women regarding dress, mobility and sexuality. For example, throughout the Muslim diaspora, the veil is making a comeback, and religion is politicizing women who were not previously civically engaged. Scholars, activists and artists continue to consider the controversy, strength and mystery of this cloth.

Finally, some women are restricted from civic, social and political participation in contexts where religious fundamentalisms are on the rise. In response, Moroccan feminist Fatima Mernissi asks, "Why do these politicians-turned-Imams come up with an anti-dignity reading of Islam focused on obedience? How come they do not see all the incredible wealth of woman-enhancing historical data they could draw on to build a human rights-nurtured Islam?" Why indeed.

Explore all the stories in this theme.