Living Between Worlds

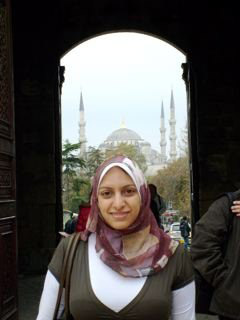

Podcast: Egyptian Women's Rights Activist Hadil El-Khouly

Still in her early 20s, Egyptian women's rights activist Hadil El-Khouly is a devout Muslim and a Feminist. She grew up in a part of the world where religion is a cornerstone of identity. It's also a place where religious fundamentalisms--Muslim, Jewish and Christian--pose significant threats to the advancement of women's human rights.

Women Power and Politics curator Masum Momaya spoke with Hadil El-Khouly in Marrakesh, Morocco, to learn about the complexities of living between worlds, the absurdities of pitting the religious against the secular, faith against feminism and Western against Eastern.

I'm still discovering this till now to be honest. The way I was brought up I had my foot in two different worlds. I was in a German school, but I was living in Cairo, two very different worlds. I use to see always the contradicting worlds, and I never lived in a bubble, so it took me a time to realize that I have multiple identities, that I'm not just an activist that I am a feminist, also.

Do you feel that having straddled two worlds has trained you see the debate in a nuanced way and to actually live in it in a more nuanced way?

I think it took a lot of time to actually situate yourself between these two worlds and to question "Do I have to be in one of them? Can I find a balance between the two?" I think the more Egyptian culture is that we tend to see anything related to Human Rights as Westernized, and this is something till today I have a problem with.

On the other hand I see Western sides sometimes interpreting things only from their perspective. I'll give you an example for that. I was once invited to talk on a lecture about FGM and there were teachers, both German and Egyptian teachers. And I was surprised to see the German teachers -- they're actually very angry at the situation -- of course we all are, but it was an attitude of "Why don't you just go to the police and report that? Why don't you just have a legal intervention?"

And I think there was a lot of misunderstanding of how difficult this actually is. That this is not a culture where you can just open the door and ask the police to run in. There is a whole different dimension of how we experience police, for example. We don't see it as a form of security, but actually another form of oppression, and it was just sometimes sad to see that.

I mean all, all different cultures even in Germany, for example, the women's rights movement, they went through these phases, and there was a phase where they had to do things in a certain way to be able to communicate to the people. And at this meeting I felt that this was a little bit forgotten, that we had achieved this now so why can't you just achieve it, but they forgot that the difficulties they went through we are going through now.

So things like that, you know, so on the one hand the problem of Human Rights always being seen as, as a Western culture that will be corrupting us and, you see, the Government plays a very negative role in that. it's always used as an excuse, this is against our culture.

So you don't feel personally a conflict between being able to hold on to your own religious beliefs and also still work very passionately for and believe in, with all your heart and soul, human rights.

For me personally no, I don't see this conflict, but I see how a lot of people thought or would expect that I am in a conflict.

To give you an example, on this same evening I was just talking about -- I'm veiled -- so at the end of the evening, one of the teachers raised a question of "How can you work for Women's Rights and be veiled?" And it was the first time for me to hear it or to actually see that it could be something someone else would question or would have a problem with. Because for me it was never a conflict.

But then I started to see that people tend to categorize you to see that it's easier for them to deal with, deal with you when I categorize you when I say you're secular, you're religious, you're feminist, I don't know, for them I think it makes it easier to deal with you, but it's unfair to you because you don't want people to fragment you. But for me I just say I'm both I'm secular and religious.

And in my struggle for Women's Rights I think that is what kept me, this belief that this is not the way it should be, and it actually helped me to have a stronger faith. And, and I could say I'm at peace with, with how I see it now.

I also see through my work how when, when you address religion, how it links people together. That as I said because it's very much politicized and people just tend to label you. It makes them feel safer, but it's unfair to you.

It seems that both institutionally and socially Islam is changing.

I wouldn't say Islam is changing, but I would say Women's Rights activists and women in general are becoming more politically aware and more demanding for space. Because for years and years and years it was always men interpreting religion for us. And I think there is a way now or a space now for, for us, because much more women are educated and because I think there is this whole political process now to fight for more democracy and to move the authoritarian systems which are of course very prevalent in the Arab world.

I think this whole movement is bringing more, an urge for justice. And the Women's Rights movement is not isolated from that, and I think this is what lead to many women to actually study Sharia and actually help other women. And for me, a lot of women were very much an inspiration for me, and to help me also to situate myself, as I was saying, that there's not only one side of the religion, there's not only one version of the truth.

And this is also happening in Egypt now. I would say that I can see now much more religious scholars, liberal female religious scholars which I can identify myself with. And I think it's not only in Egypt, but I think also the political system is; I don't know how you call it, is allowing space for that. I don't know if they're allowing or they just don't have another choice, but it's happening like for example, very recently there was a female ma'zoon. I don't know how you can explain ma'zoon. It's the state employee who writes the marriage contract. And that was always, always for men and she's the first one.

And of course there was debate about that and that there were a lot of people from the, from the religious state institutions were against that. But she's actually working now and this space is now provided for her. So I think it's this whole movement for, for political rights, for justice, for democracy, that led to this and that led women to demand more space in this.