CLIO Talks Back

Karen Offen

United States

Archive

- Jun 2011

- May 2011

- Apr 2011

- Mar 2011

- Feb 2011

- Jan 2011

- Dec 2010

- Nov 2010

- Oct 2010

- Sep 2010

- May 2010

- Apr 2010

- Mar 2010

- Feb 2010

- Jan 2010

- Nov 2009

- Oct 2009

- Aug 2009

- Jul 2009

- Jun 2009

- May 2009

- Apr 2009

- Mar 2009

- Feb 2009

- Jan 2009

- Dec 2008

- Nov 2008

- Oct 2008

- Sep 2008

- Aug 2008

- Jul 2008

- Jun 2008

- May 2008

- Apr 2008

I.M.O.W.'s debut blog, Clio Talks Back, will change the way you think about women throughout history! Be informed and transformed by Clio Talks Back, written by the museum's resident historian Karen Offen.

Inspired by Clio, the Greek muse of History, and the museum's global online exhibitions Economica and Women, Power and Politics, Karen takes readers on a journey through time and place where women have shaped and changed our world. You will build your repertoire of rare trivia and conversation starters and occasionally hear from guest bloggers including everyone from leading historians in the field to the historical women themselves.

Read the entries, post a comment, and be inspired to create your own legacies to transform our world.

Clio?s blog guest of the week: Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947).

2008-05-26 22:55:16.000

The battle for women?s suffrage in the USA was undoubtedly the most difficult, precisely because the American Constitution assigned the election laws to the states, not the federal government. Only a constitutional amendment could change this situation, and following the Civil War (1861-65) and the freeing of the slaves, negro men were legally enfranchised by the Fourteenth Amendment. But the women were written out. After decades of campaigning state-by-state, sometimes successfully and more often not, the leaders of the National Women?s Suffrage Association decided to change strategies and try for a constitutional amendment. Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt was the architect of that successful campaign for the amendment, which was ratified by the necessary number of states in 1920. Before that, even though a woman could run for president,as Victoria Woodhull did, she couldn?t vote for a presidential or congressional candidate, except in sparsely-settled states like Wyoming which had enfranchised women in 1869. Other western states had followed (including California in 1911), but the male voters and legislators of the eastern and southern states remained stubbornly hostile to the notion of woman suffrage.

Here, in the words of Carrie Catt and her collaborator Nettie Rogers Shuler, is a brief, passionate account from 1926 of what the women of the suffrage movement in the United States did, over the course of some seventy years (from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920) of campaigning for the vote:

"Three years were consumed in the process of writing the word male into the Federal Constitution, two more in completing the enfranchisement of the Negro. Both were strictly Republican party measures and were achieved by the combined political force of a majority party and the military power of the nation. The demand to include women in any further extension of the suffrage, although supported at the time by men of great influence in party and nation, was effectually evaded all along the way by the proposal to 'let the women wait ? this is the Negro?s hour, -- the woman?s hour will come.'?

"To get the word male in effect out of the constitution cost the women of the country fifty-two years of pauseless campaign thereafter. During that time they were forced to conduct fifty-six campaigns of referenda to male voters; 480 campaigns to urge Legislatures to submit suffrage amendments to voters; 47 campaigns to induce State constitutional conventions to write woman suffrage into State constitutions; 277 campaigns to persuade State party conventions to include woman suffrage planks; 30 campaigns to urge presidential party conventions to adopt woman suffrage planks in party platforms, and 19 campaigns with 19 successive Congresses. Millions of dollars were raised, mainly in small sums, and expended with economic care. Hundreds of women gave the accumulated possibilities of an entire lifetime, thousands gave years of their lives, hundreds of thousands gave constant interest and such aid as they could. It was a continuous, seemingly endless, chain of activity. Young suffragists who helped forge the last links of that chain were not born when it began. Old suffragists who forged the first links were dead when it ended."

Clio wonders: How could we forget a campaign that was so costly in time and energy? How could it be that every citizen, male or female, does not cherish and exercise the right to vote, won at so great a cost?

Clio says: No citizen, female or male, can ever take for granted the right to express political opinion, wherever that right exists.

Source: Carrie Chapman Catt & Nettie Rogers Shuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (New York: Charles Scribner?s Sons, 1926) ? from Chapter IX ? ?The Woman?s Hour that Never Came,? pp. 107-110. Quotes pp. 106-7.

Clio contemplates the gender of power: Filipino origin myths.

2008-05-17 11:51:59.000

A colleague in Australia, Mina Roces, studies symbols of power and insightfully analyzes the gender (masculine/feminine) of power and its function in the Philippines:

?In the Filipino perception of power the concept that fuses both the practice of considerable power and the prestige that that power entails, is the concept of malakas. Malakas is literally translated as strong. In a political sense a person who is malakas is one who in a position of power would use that power unscrupulously to benefit his/her kinship group. One who does not want to use his/her position or power to help his/her kin group is mahina (weak). And to be branded mahina ka (you are weak) is pejorative. Thus, one's being malakas or mahina becomes a culturally-defined yardstick of a person's prestige, power and influence.

?Although the mythological origins of the concept of malakas is gender specific, (the Philippine myth of origin is that man and woman emerged equally out of a bamboo that was split, with the man called malakas (strong) and the woman called maganda (beautiful), it is non-gendered in practice. Both men and women can be perceived as having malakas status regardless of whether they possess official power or not. It is in this practice of palakasan (which one sociologist has defined as the competition for favours based on power) that a woman, denied access to the symbols of official power can in fact possess actual power. The malakas concept implies one's closeness to the powers that be (as well as the ruthless exercise of power). Power in the Philippines context is perceived to be tied up with the kinship group. The brother of the president is malakas just as the wife of the president is malakas. Even employees of the president are considered malakas. Power is not just concentrated on the individual official but perceived to be held in varying degrees by his kinship group. Malakas therefore must be interpreted in kinship alliance terms. And thus, it is through their kinship ties with male politicians that women exercise power.?

Clio adds: Roces?s insights apply particularly to the power women can wield in governance based on kinship ties. She considers the examples of Imelda Marcos and Corazon Aquino. The analysis she develops could also apply to Indira Gandhi in India, Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan, and the mother-daughter team who attained high political office in Sri Lanka/Ceylon. It also illuminates the function of power in ancien regime France and certain other Western monarchies, where for centuries the male-dominated power structure worked hard to disqualify women from exercising formal power ? except as regents for their sons. The gendered notion of malakas may also help explain the discomfort that exists in the USA around the power attributed to ?First Ladies.? It can also help us understand why feminist demands became so much more intense in the democratizing West as individuals, not family dynasties, came to the fore as political players.

Source: Mina [Maria Natividad] Roces, ?Can Women Hold Power Outside the Symbols of Power?? Asian Studies Review [Australia], 17:3 (April 1994), 14-23; quote pp. 17-18.

Clio considers Parliaments of women

2008-05-10 11:37:30.000

Ever since the Greek playwright Aristophanes wrote and staged his comedy, the Parliament of Women, in ancient Athens, critics have worried about the implications of women meeting to discuss and take action on issues of mutual concern. One of the most radical demands by women during the early years of the French Revolution was that they wanted separate representation, even a separate assembly in the Estates-General. These women demanded inclusion in the French nation as full-fledged Citoyennes. Since then, the question of women?s political activity has sparked much discussion in various parts of our world.

In 1848, the women who convened the first American women?s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York, invoked the example of the local Iroquois Indians, where women participated in the decision-making of the tribe, to bolster their own claims for political rights and participation. They objected strenuously to the notion that men should do all the decision-making.

In our own time, in democratic or democratizing nations, women have demanded parity in the representation of women in political assemblies. But for a long time, even in Western countries, men strongly opposed the notion that women should sit and deliberate alongside them; they might be ?distracted? from official business! After Finnish women won the vote in 1906 (the first in Europe, even before the Norwegians), Finnish women representatives sat down with Finnish men in the first Finnish parliament. This was unprecedented!

In the meantime, in 1888, a small group of progressive women founded the International Council of Women/Conseil International des Femmes. This effort, spearheaded by May Wright Sewall, quickly grew. Sewall?s ultimate vision was to establish a ?Permanent International Parliament of Women,? ?where not only the questions which are supposed peculiarly to concern womanhood shall be discussed, but where all the great questions that concern humanity shall be discussed from the woman?s point of view.?

Beginning with the World?s Congress of Representative Women, which Sewall organized in 1893 during the World?s Fair in Chicago, and again in London in 1899 and Berlin in 1904, these meetings quickly acquired the label of ?women?s parliaments.? They attracted thousands of participants, from all corners of the globe. Other budding international organizations, dedicated to promoting peace or socialism, had invited women to participate and to speak, but even in those settings, women participants felt the need to meet separately, especially so they could discuss ?women?s issues? in relation to peace and socioeconomic change. Perhaps the only exception to this rule was the International Abolitionist Federation, which was a ?mixed? (men and women) organization from its beginnings in the 1870s. Its goal was to eradicate government regulated prostitution. Today the tradition of women?s parliaments continues with the ?Global Summit? for women, organized by Irene Natividad (an IMOW Global Council member) continuing the huge women?s international conferences sponsored by the United Nations between 1975 (Mexico City) and 1995 (Beijing).

Of course, not all meetings of women to discuss change take place in parliaments or in national or international congresses. Women around the world have often felt the need to meet for discussion and to plan action for social and political change. They meet around kitchen tables, or their equivalents such as washhouses and wells, in local settings. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo exemplify this tradition. Many other such efforts remain to be documented. But Clio is sure that women?s political power emerges from collective as much as from individual efforts.

How and when do such ?parliaments? of women, small and large come together in your part of the world? and how do such meetings achieve their goals? What can we learn from their examples? Clio welcomes your thoughts about parliaments of women, both small and large, in the past and in the present.

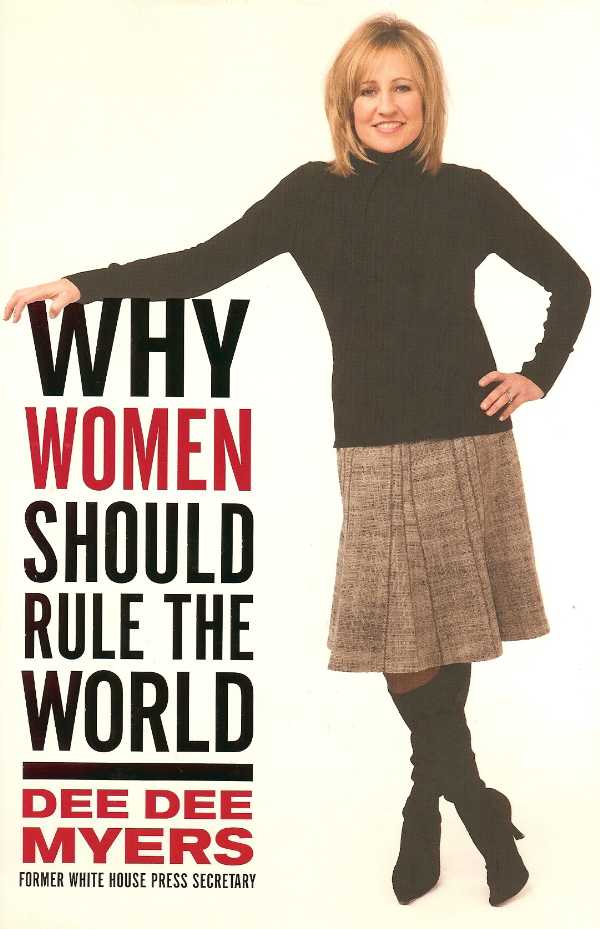

Clio considers why women should rule

2008-05-08 09:39:39.000

In a new book, a former White House press secretary named Dee Dee Myers proposes ?Why Women Should Rule the World.? First she discusses why women don?t rule the world, then why women should, and finally ? how women can rule the world.

Dee Dee Myers takes a lot for granted. Such as that women have a perfect right to participate fully in the political process. This is not a given in many societies today, even in countries where women do have the right to vote. Women candidates have been successful at the local level, but getting elected to office at the national level has proved difficult, a problem that women have addressed in parliamentary monarchies such as Norway with quotas, and in the French Fifth Republic with a constitutional amendment on parity in representation. Running and winning at the national level in countries like the USA, with single-member constituencies and election rules that differ from state to state, has proved difficult and expensive.

One of Myers?s topics in the final part of the book is ?Closing the Confidence Gap,? which begins with a wonderful quotation from one of America?s most significant first ladies, Eleanor Roosevelt, who insists that ?Nobody can make you feel inferior without your permission.? And Dee Dee Myers insists that ?it?s up to women to change the dynamic,? ?to write a new script,? to demand the resources they need and take credit for their achievements. She also talks about the importance of role models for girls. In fact there is an entire section on younger women who took extraordinary action for change because they had been inspired by an older woman they knew or a historical figure they admired. They read biographies of women and men, they went to hear newsworthy women speak, they asked for autographs and shared their hopes and dreams. Just like you?.

?The bottom line,? says Myers, is that ?The more women succeed, the more women succeed.? ?Sometimes, it takes one woman; sometimes, it takes many. Almost always, I?ve found, when there are enough women in the room so that everyone stops counting, women become free to act like women.? And once that happens, women can bring ?a different range of experiences, skills, and strengths to public life? and we ?can expand our definition of leadership ? and of the language we use to describe it.? In closing, Myers insists that when women rule, ?we will have changed the very definition of power.? It?s high time we did!

This is worth thinking about, wherever in the world we live. But it can only happen one step at a time, until there is a ?critical mass? of women in the decision-making room. Until then, we have to do like the storybook figure of the ?little engine that could? ? faced with climbing that steep hill the little engine said ?I think I can, I think I can, I think I can? and she went faster and faster until she did!

Source: Dee Dee Myers, Why Women Should Rule the World (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008).