CLIO Talks Back

Karen Offen

United States

Archive

- Jun 2011

- May 2011

- Apr 2011

- Mar 2011

- Feb 2011

- Jan 2011

- Dec 2010

- Nov 2010

- Oct 2010

- Sep 2010

- May 2010

- Apr 2010

- Mar 2010

- Feb 2010

- Jan 2010

- Nov 2009

- Oct 2009

- Aug 2009

- Jul 2009

- Jun 2009

- May 2009

- Apr 2009

- Mar 2009

- Feb 2009

- Jan 2009

- Dec 2008

- Nov 2008

- Oct 2008

- Sep 2008

- Aug 2008

- Jul 2008

- Jun 2008

- May 2008

- Apr 2008

I.M.O.W.'s debut blog, Clio Talks Back, will change the way you think about women throughout history! Be informed and transformed by Clio Talks Back, written by the museum's resident historian Karen Offen.

Inspired by Clio, the Greek muse of History, and the museum's global online exhibitions Economica and Women, Power and Politics, Karen takes readers on a journey through time and place where women have shaped and changed our world. You will build your repertoire of rare trivia and conversation starters and occasionally hear from guest bloggers including everyone from leading historians in the field to the historical women themselves.

Read the entries, post a comment, and be inspired to create your own legacies to transform our world.

Records of the WILPF, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Parading the petitions to the conference

Records of the WILPF, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Peace women walking to the Peace Congress, Geneva 1932

The women?s peace petition at the World Disarmament Conference, Geneva, 1932

2008-10-24 12:20:40.000

A time-honored way for women in industrializing societies to express their political views or demand political change was by petitioning their governments, and later international organizations. Petitions demanding the end of slavery represented a significant number, as did petitions to end married women?s legal disabilities, to claim access to the vote, and ultimately to demand peace. A few examples follow.

In 1853, British women presented a petition against slavery, addressed to the women of the United States, and signed by 500,000 women. The organizers of this petition presented it to the famous antislavery novelist, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the best-selling novel, Uncle Tom?s Cabin.

In 1885, 15,000 women petitioned the Dutch parliament to put a halt to trafficking in women.

In 1919, Japanese women associated with the New Woman Association (Shin Fujin Kyokai) petitioned the parliament (Diet). They first demanded citizenship for women, including the vote. Then they called on the state to protect women by requiring men to be tested, before marriage, for syphilis, and permitting already infected wives to sue for divorce and collect monetary compensation for medical expenses incurred as a result.

In Europe, following the unprecedented killing and devastation of World War I, women activists from many countries, including some in which women did not yet have a vote, worked to understand the causes of war and to seek its prevention. The Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, devoted to outlawing war forever, gave them great hope, but the signers of the agreement seemed to honor it only by ignoring it.

In anticipation of the World Disarmament Conference (held in Geneva beginning in early February 1932), a joint Disarmament Committee of the Women?s International Organizations represented at the League of Nations launched a worldwide campaign to collect signatures for a huge petition for peace. They gathered signatures from eight million women in fifty-six countries around the world; of those, six million had been gathered by the Women?s International League for Peace and Freedom (W. I. L. P. F.), headquartered in Geneva. Rosa Manus of the Netherlands coordinated this enormous effort.

On the sixth of February, 1932, the women?s committee delivered truckloads of petitions for peace and disarmament to the floor of the disarmament conference. This dramatic action, preceded and succeeded by public exhibit of the petitions, attracted considerable coverage in the press. The impact of this women?s initiative was heightened by news that Japanese planes were dropping bombs on Shanghai, China ? a premonition of what might soon happen elsewhere in the world..

Presenting the petitions on the floor of the assembly to a mostly-male audience, Mary A. Dingman, president of the World?s Young Women?s Christian Association, declared:

?Behind each of these names stands a living personality, a human being, oppressed by a great fear, the fear of the destruction of our civilisation, but also moved by a great will for peace, that cannot be ignored and must not be denied.?

The women organized a great demonstration that afternoon, and continued to sponsor events emphasizing their determination to forward peace.

Unfortunately the World Disarmament Conference failed to produce the desired results, and the build-up of armaments by many countries continued through the 1930s, ultimately erupting in what we know as World War II, where fighting took place in virtually every part of the world. The women of W.I.L.P.F., joined then and since by many other groups, continued to agitate for disarmament and peace, and still do so today.

Source: Miss Dingman?s remarks, as quoted in Adele Schreiber, ?Woman at the Disarmament Conference,? Jus Suffragii, 26:6 (March 1932), 55. Jus Suffragii was the publication of the International Alliance of Women (known before 1926 as the International Woman Suffrage Alliance), one of the members of the Joint Committee of Women?s International Organizations represented at the League of Nations.

See also: Pax International 7:4 (March 1932). Pax International was the publication of the Women?s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Online Exhibit of W.I.L.P.F. at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection. www.swarthmore.edu/Library/peace/Exhibits/wilpfexhibit/exhibithome.htm

International Headquarters: www.wilpf.int.ch

Collection of Karen Offen

Spanish women voting for first time

Collection of Karen Offen

Statue of Clara Campoamor, Madrid, visit by Rosa Capel Martinez & Clio 2006

Women deputies debate whether women should vote ? Spain 1931

2008-10-15 14:47:48.000

With the fall of the monarchy and the proclamation of the Second Republic in April 1931, the issue of political rights for Spanish women surged to the forefront. As in republican France since the revolution of 1789, female figures dominated revolutionary symbolism and ?Liberty? led the people. But (as in France) Spanish women did not have the right to vote in national elections.

The Spanish Constituent Assembly (Cortès Constituyentes) opened on 14 July (the French Bastille Day) 1931. Secular Liberals insisted that the incorporation of equal rights for women would crown Spain's emergence as a modern, secular, democratic European nation. In May the new government authorized women who met certain qualifications to stand for office, along with priests and government employees. The Second Republic initially adopted a system of proportional representation, modelled on that of Weimar Germany, with electoral lists that favored party formation.

In the absence of woman suffrage, however, few parties sought to address issues that women cared about; this was clear from complaints expressed in late June in L'Opinio by a Catalan women's group:

?It is time to end flattering promises. There have been some for everybody except us. The candidates and their friends have had this lapse which may come to be regretted. Only Esquerra Catalana has remembered to say that it will accord careful protection to mothers and children. That is not what we want: we do not ask for protection; we want our rights to be recognized and equal to those of men. Now that it is time to structure a people, let it not seem that there are only men on earth.?

In June two distinguished Spanish women were elected as deputies (out of 470 seats) to the Cortes Constituyentes: Clara Campoamor Rodríguez (1888-1972) represented the Radical Party, and Victoria Kent Siano (1892-1987), the Radical Socialist Party.

Members of the Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Españolas (National Association of Spanish Women, ANME; founded 1918) campaigned vigorously for inclusion of the women's vote in the new republican constitution. So did Spanish Catholics, on the grounds that women's vote would prove beneficial - as indeed it had in other dominantly Catholic post-war nations - to the socially conservative program of the church. This was precisely what skeptics among the strongly secular Liberal Republicans - and Socialists - feared, however much they may have supported the concept of equal suffrage in principle. Fear of women outnumbering men, their illiteracy, and the threat of clerical influence on their politics dampened the enthusiasm of men on the Left who should, in theory, have been most supportive.

During the constitutional debates of 1 October 1931, the public was treated to a floor fight between the two women deputies, Clara Campoamor and Victoria Kent, over the paragraph that became Article 36, on the subject of women's political rights. This debate between two women deputies over women's voting was a political "first." Campoamor, an attorney who served on the constitutional commission and also represented the new Republic of Spain to the League of Nations, argued the pro-suffrage position, and Kent, the first woman lawyer in Spain and a well-known defense attorney who had been appointed director-general of the Spanish prison system, argued against women's immediate enfranchisement, which she nevertheless supported in principle.

Victoria Kent argued that Spanish women were not "ready" and that enfranchising them immediately would endanger the very survival of the fragile republic. She had seen little evidence of women's mobilization on the new regime?s behalf: ?I believe that . . . postponement would be the most beneficial . . . it is dangerous to concede the vote to women.?

Clara Campoamor rebutted Kent, arguing from principle. In earlier debates she had insisted on showcasing the opportunity available to Spain to take the lead among the Latin countries of Europe in enfranchising women. She had also fended off an attempt to take the equal suffrage clause out of the constitution, placing it instead in a more easily changed electoral law. Against Kent she pointed out, amid heckling from her own male party colleagues, that the same criticisms Kent made of women were also true of many men, yet nobody pointed to them or threatened to withdraw their vote: ?Precisely because the Republic means so much to me, I understand what a grave political error it would be to cut women out of the right to vote.?

?Do not forsake the woman who, if she is not progressive, places her hope in the Dictatorship, or the woman who thinks, if she is progressive, that her hope for equality can only be achieved in Communism. Do not commit, Honourable Deputies, a political error which has such grave consequences. Save the Republic, support the Republic by attracting and drawing into it this female force which anxiously awaits the moment of redemption.?

The motion to enfranchise women passed by a margin of 161 to 121, with 183 male deputies absenting themselves, including the Socialists.

The new constitution of the Second Republic, ratified in December 1931, did enfranchise all women and men over the age of twenty-three. It also separated church and state, secularized marriage law and introduced civil divorce, and initiated a host of other dramatic and potentially radical changes in Spanish civic life, including the outlawing of regulated prostitution. Thus did the republican government, liberal and emphatically secular, if not adamantly left-wing, antagonize the conservative and authoritarian forces on the Right.

The ensuing 1933 elections were a disaster for the republicans. Not surprisingly, many on the Left blamed women's votes for these results. The republic's difficulties increased dramatically, and the forces of the Right began to organize their challenge.

In July 1936 civil war broke out, following the mutiny of troops behind General Francisco Franco, in the name of what came to be called "national Catholicism" Both the republican and the monarchist factions quickly began to receive infusions of materials, manpower, and advice from the USSR (on the republican side) and from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany (on Franco's side), in addition to assistance - and sometimes interference - from various other enthusiastic left-wing European and even North American nationals.

That year Clara Campoamor sorrowfully left Spain for exile abroad. Going against her own party's position on woman suffrage had effectively derailed Campoamor's political career. Victoria Kent became the Spanish ambassador to France, but ended up in hiding during the German occupation. She too took the road to exile, first to Mexico, and then to New York. Franco?s authoritarian regime endured into the 1970s.

Sources: Text adapted from Karen Offen, European Feminisms 1700-1950 (Stanford University Press, 2000). See also: Rosa Maria Capel Martinez, El sufragio femenino en la Segunda Republica Española, 2nd ed. (Madrid: Horas y horas, 1992); Danièle Bussy-Genevois, "The Women of Spain from the Republic to Franco," in Toward a Cultural Identity in the Twentieth Century, ed. Françoise Thébaud (Harvard University Press, 1994); Judith Keene, "'Into the Clear Air of the Plaza': Spanish Women Achieve the Vote in 1931," in Constructing Spanish Womanhood: Female Identity in Modern Spain, ed. Victoria L. Enders & Pamela B. Radcliff (SUNY Press, 1998), and Rosa Maria Capel Martinez, ed., Historia de una conquista; Clara Campoamor y el voto femenino (Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid, Dirección General de Igualdad de Oportunidades, 2007).

See also the entries on Campoamor and Kent in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History (2008).

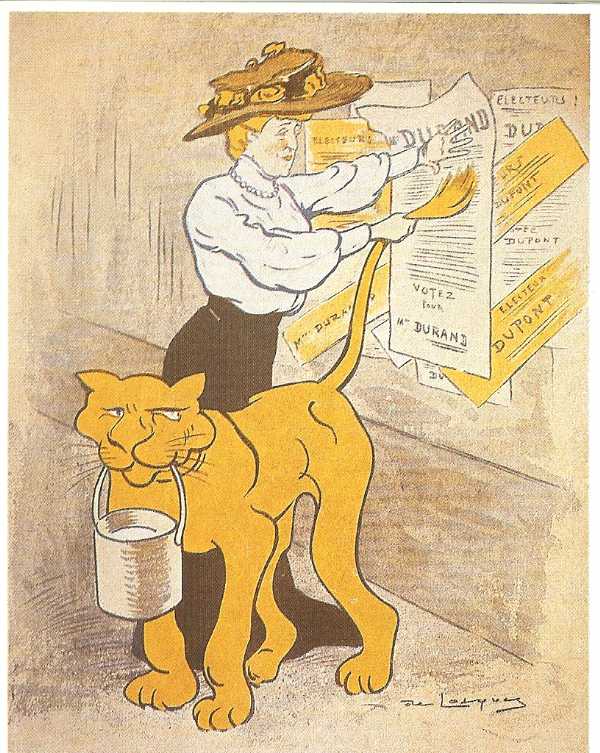

Cover of L'Illustration, #3501 (2 April 1910).

Marguerite Durand campaigning 1910

Postcard, Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand, Paris

Marguerite Durand with Tigger, putting up campaign posters

A French feminist runs for the Chamber of Deputies, 1910.

2008-10-05 21:41:34.000

In 1910 the French journalist and political activist Marguerite Durand declared her candidacy for election to the national Chamber of Deputies from the ninth arrondissement (district 2) of Paris.

She was not the first women to run for the deputation ? that honor belonged to the French feminist and woman suffrage advocate Jeanne Deroin, who posed her candidacy in 1849, also in Paris. However, neither in 1849 nor in 1910 were French women authorized to vote or to run for public office. The constitutions of both the Second (1848-1851) and Third Republics (1875-1940) specified that the vote was for ?les français,? a masculine noun that in French could include all men and women, or not, depending on how it was interpreted, which was usually against the inclusion of women as separate individuals. The so-called ?universal suffrage? established in 1848 in fact was ?universal manhood suffrage?only ? and this situation lasted, despite great efforts by the suffragists, until 1944. Why? because French republican men feared that the vast majority of women might vote with the Catholic priests and topple the already insecure republic.

French women began to campaign in earnest for the vote following the establishment of the Third Republic. Hubertine Auclert launched her newspaper La Citoyenne in which she and her supporters campaigned vigorously for the vote on the same terms as men ? every one of whom were enfranchised at every level, municipal, departmental, and national. But the legislatures refused to take up women?s suffrage proposals up till 1900, and then only at the municipal level. At that point, women were voting in New Zealand, Australia, and in many western states in the United States. And in early twentieth century England, women launched a formidable campaign for the vote (see Clio?s August blog on Lady Constance Lytton and the Women?s Social and Political Union).

By the time Marguerite Durand declared her 1910 candidacy and began to campaign, she had years of experience of agitating and organizing for change in French civil society. An anticlerical radical feminist, her most important contribution was to found La Fronde, a daily newspaper staffed entirely by women, from the reporters on foreign affairs and the stock market to the typsetters and distributors. Durand then concerned herself especially with issues concerning women?s employment. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, French reformers (male) became very agitated about the declining birthrate in France and blamed it on women?s efforts to emancipate themselves. Most feminists ridiculed such assumptions, even campaigning for an improved climate and conditions for motherhood.

French feminists emphasized both function and style, not merely to acknowledge that they appreciated the seriousness of men's concern for the population problem but also as a realistic means of promoting desired legal reforms in the absence of the vote. Marguerite Durand?s 1910 campaign platform epitomizes this approach.

To focus attention on the question of women?s vote, shortly after the founding of the French Union for Women?s Suffrage in 1909, Durand advocated a number of significant reforms that could improve women?s lives: (1) obligatory child-care and housekeeping instruction in all girls' public secondary schools (lycées); (2) recognition of (and payment for) household work done in the home; (3) equal pay for equal work; (4) obligatory humanitarian service for all women (except those who were already mothers) as long as military service was required for men; (5) modification of laws that render women inferior in the married state; (6) maternity insurance; and (7) access for women to all schools, careers, professions, functions, and public charges for which their aptitudes and capacities permit them to compete.

This was a dramatic and radical program in 1910 and it took many more years to realize most of these goals.

Marguerite Durand went on to found the women?s history library in Paris that bears her name ? the Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand ? one of the most important feminist archives in the world.

And, yes, Marguerite Durand did keep a pet tiger!

Source: Announcement of election meeting, 13 April 1910. ?Réunion publique et contradictoire. Madame Marguerite Durand et le citoyen Charles Marest, candidats aux élections législatives dans le IXe arrondissement exposeront leurs programmes.? Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand.

Further reading: Karen Offen, ?Women, Citizenship, and Suffrage in the French Context, 1789 1993,? Suffrage and Beyond: International Feminist Perspectives, ed. Melanie Nolan and Caroline Daley (Auckland: Auckland University Press; co published with New York University Press & Pluto Press, London, 1994), 151-170. Mary Louise Roberts, ?Acting Up: The Feminist Theatrics of Marguerite Durand,? in The New Biography: Performing Femininity in Nineteenth-Century France, ed. Jo Burr Margadant (University of California Press, 2000), 171-217.