CLIO Talks Back

Karen Offen

United States

Archive

- Jun 2011

- May 2011

- Apr 2011

- Mar 2011

- Feb 2011

- Jan 2011

- Dec 2010

- Nov 2010

- Oct 2010

- Sep 2010

- May 2010

- Apr 2010

- Mar 2010

- Feb 2010

- Jan 2010

- Nov 2009

- Oct 2009

- Aug 2009

- Jul 2009

- Jun 2009

- May 2009

- Apr 2009

- Mar 2009

- Feb 2009

- Jan 2009

- Dec 2008

- Nov 2008

- Oct 2008

- Sep 2008

- Aug 2008

- Jul 2008

- Jun 2008

- May 2008

- Apr 2008

I.M.O.W.'s debut blog, Clio Talks Back, will change the way you think about women throughout history! Be informed and transformed by Clio Talks Back, written by the museum's resident historian Karen Offen.

Inspired by Clio, the Greek muse of History, and the museum's global online exhibitions Economica and Women, Power and Politics, Karen takes readers on a journey through time and place where women have shaped and changed our world. You will build your repertoire of rare trivia and conversation starters and occasionally hear from guest bloggers including everyone from leading historians in the field to the historical women themselves.

Read the entries, post a comment, and be inspired to create your own legacies to transform our world.

What is Women?s History?

2009-02-21 16:16:53.000

Here is how Clio defines "women's history":

?Women?s history encompasses the history of humankind, including men, but approaches it from a woman-centered perspective. It highlights women?s activities and ideas and asserts that their problems, issues, and accomplishments are just as central to the telling of the human story as are those of their brothers, husbands, and sons. It places the sociopolitical relations between the sexes, or gender, at the center of historical inquiry and questions female subordination. It examines the closely intertwined constructions of femininity and masculinity over time in one or more cultures, looking for evidence of continuities and changes. It also exposes and confronts the biases of earlier male-centered historiography, asking why certain subjects and choices of themes for study were favored over others and posing new questions for investigation. Women?s historians have expanded the scope of research on women and gender both temporally, from prehistory to the present, and geographically, from dealing only with the West to encompassing the globe.?

For more, see Karen Offen, ?History of Women,? in vol. 2, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History, ed. Bonnie G. Smith. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Why Do Women (and Men too) Need Women?s History?

2009-02-18 23:05:21.000

Clio notes that in the USA, the month of March is Women?s History Month, as designated by the Congress of the United States (this, too, was a struggle). So it?s time to think about why we need women?s history ? and particularly why we need to know about the history of women?s struggles for liberty, equality, and justice. Clio has gathered a collection of interesting quotations on this subject from historians around the world. Here is a sample from the 1990s.

"The year Zero: this is a striking title. Before 1970 nothing happened? Women had never demanded anything? Unthinkable. Then what is the sense of this affirmation? Must one get rid of the past? Why? Should one avoid wasting one's time acquiring knowledge of it? Could one affirm, a priori, that we had nothing to learn from the past?

Hedwig Peemans Poullet (Belgium), 1991

"Feminism should be added to the political history...as an autonomous political movement, next to the liberal, socialist (or social democratic) and religious parties."

Marianne Braun (The Netherlands), 1992

"History is not simply what happened in the past but, more pointedly, the kinds of knowledge about the past that we are made aware of."

Antoinette Burton (USA), 1992

"The historiography of feminism is hampered by . . . lack of a functioning feminist tradition transmitted from one generation to the next. . . . Few of those who have protested about women's oppression in any given generation have known about predecessors and even those who did rarely acknowledged them."

Barbara Caine (Australia), 1995

The loss of collective memories, of myriad stories about the past, has contributed greatly to the ongoing subordination of women. The unending, cumulative building of broadly defined histories of women, including histories of feminism, is a critical component of resistance and change."

Susan Stanford Friedman (USA), 1995

"Time and again, the conclusion imposes itself that the amount of feminist activity over the past six centuries has been consistently underestimated, even by historians sympathetic to the feminist cause. . . . The question is not, in our opinion at least, whether we ought to reconstruct a history of European feminism(s), but how we may do so."

Tjitske Akkerman & Siep Stuurman (The Netherlands), 1998

Bibliotheque Marguerite Durand, Paris

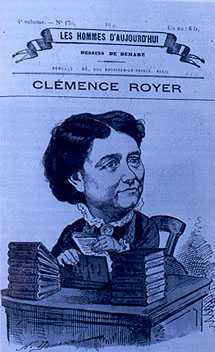

Clemence Royer as a young woman

from Les Hommes d'Aujourd'hui 1881

Clemence Royer - Caricature 1881

What Did Darwin Say about Women?s Emancipation? And Why Don?t We Hear More about Clémence Royer?

2009-02-08 13:22:23.000

All around the western world, scientists, museums, and others are celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), the English scientist whose Origin of Species (1859) forever changed the way we think about evolution and set off a huge protest by fervent Christians threatened by the notion that creation was not entirely the work of God, accomplished in six days some 6000 years earlier, and authoritatively documented in the Bible. Conflicts between defenders of Biblical creation and advocates of evolution filled the press for years thereafter. Not only that, but the very thought that man might have descended from the apes made traditionalists extremely nervous.

But Origin had not directly broached another subject that was already on many people?s minds from the 1830s ? the evolution of humankind and the emancipation of women. What did Darwin say about women?s emancipation?

Darwin clarified his views on human evolution in a new landmark work, The Descent of Man (1871). There he proposed the evolutionary importance of sexual selection, or choice of mate, for increasing the differentiation between men and women ? not only physiologically but also mentally and emotionally. Darwin was no misogynist but found it difficult to accept the arguments for women?s emancipation of such liberal thinkers as John Stuart Mill, author of The Subjection of Women (1869) and proponent of woman suffrage in the British Parliament a few years earlier. In Darwin?s eyes, historically speaking, women, however much preyed upon by men, had become increasingly protected by them as societies grew more complex. This suggested to him that women had lost the necessity of having to sharpen their faculties in the unremitting struggle for survival, thereby assuring their relatively inferior development; he was convinced that the results of evolutionary sexual differentiation could never be undone, whatever 19th century women?s rights advocates might desire.

This set off a stream of scientific investigations by physicians and others to measure skulls found in anthropological digs and to hypothesize about the relative size of women?s and men?s brains; these were the early years of physical anthropology. Some years later other scientists, such as Dr. Léonce Manouvrier, took women?s side, pointing out that relative to women?s body size, their brains might actually be larger than men?s. Partisans in controversies over providing secondary and higher education for women invested heavily in these arguments, on both sides of the question.

Darwin?s Origins was translated into French by a remarkable self-taught woman scientist, Clémence Royer (1830-1902), who was still a baby when the young Darwin set off on his voyages of exploration that led to his evolutionary theses. She undertook this labor because she said Darwin?s earlier work confirmed her own theories. Royer was already known for proposing (in the 1850s, in Lausanne) a ?woman?s philosophy,? She sought ?a form, a feminine expression of science. . . . a new art that I have to create.? ?As long as science remains exclusively in the hands of men,? she explained, ?it will never go down into the depths of the family and society. . . . Why. . . should [women] be excluded from the hunt for truth?? In 1869 Royer published a book, Origine de l?homme et des sociétés (The origins of man and of societies), nearly 600 pages long.

In the 1870s Clémence Royer joined the Anthropological Society in Paris and waded in on these debates, insisting that male scientists ?have a disposition to find sexes everywhere,? and critiqued their ideas about sexual polarization. ?Woman . . . is the one animal in all creation about which man knows least,? she exclaimed. Her long exposition, ?On the Birthrate,? which addressed the subject of women, their needs, desires, and reforms required, was suppressed. Even after it was typeset, it was considered too explosive to publish, and the manuscript, along with the galleys and page proofs lay quietly in the archives of the Anthropological Society until their rediscovery in the late 20th century. Joy Harvey has translated the document into English, publishing it in her 1997 biography of Clémence Royer. Clio thinks Royer's contributions ought to be far more widely known.

Sources:

Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents, vol. 1, 1750-1880, ed. Susan Groag Bell & Karen Offen (Stanford University Press, 1981), which reprints the critical passages from Darwin?s Descent of Man, along with published remarks from Paul Broca and Herbert Spencer. Two recent biographical studies are: Genevieve Fraisse, Clémence Royer: Philosophe et femme de sciences (Paris, 1985) and Joy Harvey, ?Almost a Man of Genius?: Clémence Royer, Feminism, and Nineteenth-Century Science (Rutgers University Press, 1997). See also Sara Jane Miles, ?Evolution and Natural Law in the Synthetic Science of Clémence Royer, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicato, 1988, which includes translations of a number of Royer texts; and Linda L. Clark, Social Darwinism in France (University of Alabama Press, 1984).