CLIO Talks Back

Karen Offen

United States

Archive

- Jun 2011

- May 2011

- Apr 2011

- Mar 2011

- Feb 2011

- Jan 2011

- Dec 2010

- Nov 2010

- Oct 2010

- Sep 2010

- May 2010

- Apr 2010

- Mar 2010

- Feb 2010

- Jan 2010

- Nov 2009

- Oct 2009

- Aug 2009

- Jul 2009

- Jun 2009

- May 2009

- Apr 2009

- Mar 2009

- Feb 2009

- Jan 2009

- Dec 2008

- Nov 2008

- Oct 2008

- Sep 2008

- Aug 2008

- Jul 2008

- Jun 2008

- May 2008

- Apr 2008

I.M.O.W.'s debut blog, Clio Talks Back, will change the way you think about women throughout history! Be informed and transformed by Clio Talks Back, written by the museum's resident historian Karen Offen.

Inspired by Clio, the Greek muse of History, and the museum's global online exhibitions Economica and Women, Power and Politics, Karen takes readers on a journey through time and place where women have shaped and changed our world. You will build your repertoire of rare trivia and conversation starters and occasionally hear from guest bloggers including everyone from leading historians in the field to the historical women themselves.

Read the entries, post a comment, and be inspired to create your own legacies to transform our world.

Louise Bourgeois, midwife extraordinaire

2011-03-08 18:12:15.000

Today?s guest blog on the French midwife Louise Bourgeois is contributed by Clio?s longtime colleague, historian Alison Klairmont Lingo, at the University of California, Berkeley.

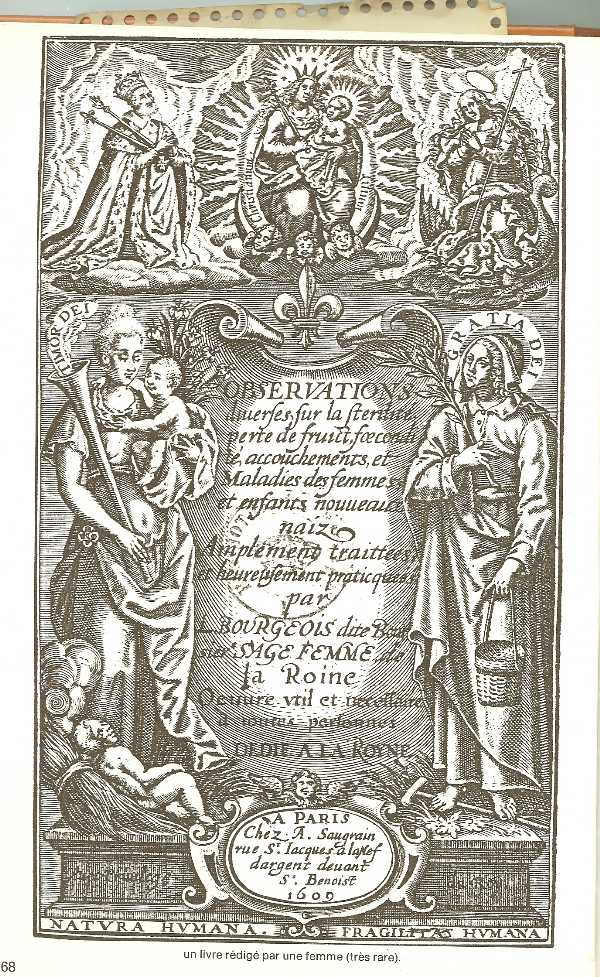

?Louise Bourgeois (1563-1636), French midwife extraordinaire, was the first woman to publish a medical treatise on childbirth and women?s illnesses (1609). In her capacity as royal midwife to queen Marie de Médicis, the second wife of King Henri IV, she also had the honor of delivering the future king Louis XIII, thus ensuring peace and stability in France by facilitating the birth of a healthy male heir for the Bourbon dynasty. Only males could succeed to the French throne.

?Born into a wealthy, property-owning family living just outside the city gates of Paris, her life fell apart in 1589 during the religious civil wars when mercenary troops reduced everything in her neighborhood to rubble, including her home and other family properties. With her surgeon husband already at the front, Bourgeois fled to safety within Paris with her mother and three small children.

?Upon her arrival in Paris, Bourgeois eked out an existence by doing needlepoint, her only marketable skill, and by selling personal property. She discovered her medical calling by chance when a honneste femme; i.e., an unlicensed midwife who had delivered her children, counseled her to become a midwife. Bourgeois? reading skills and connections to the medical world through her surgeon husband made a career in midwifery a natural choice, the older woman told her. Reluctant at first to engage in a craft, perhaps because it seemed lowly to her, perhaps because of the responsibility for human life it entailed, Bourgeois considered the woman?s advice more seriously once economic necessity forced her to do so.

?Bourgeois trained herself by reading the works of the famous royal surgeon Ambroise Paré who had reintroduced birthing techniques for delivering malpresenting babies without the use of crochet hooks or knives, as was the usual practice. She then began delivering the children of women from her district. Word spread of her skill until ultimately she rose to the position of royal midwife, a post she acquired through a vast networking scheme that called upon her aristocratic clients, their husbands, and the royal physicians who had recommended her to Marie de Médicis.

?Clearly Bourgeois benefitted financially by becoming royal midwife. The celebrity and confidence that the king and queen bestowed upon her resulted in a payment to her of 900 livres for four royal births, an amount more than eight times that of the average yearly salary of a sage-femme pensionnée (a salaried midwife hired by a municipality). Eventually the king settled upon a yearly pension of 300 écus, a goodly amount when compared to the 26 livres a year made by midwives in the city of Nevers in 1602. Thus, in 1605, Bourgeois and her husband were able to buy a house in Paris to replace the one they had lost during the civil war, a.k.a., the ?troubles.? They were still living there during the second decade of the seventeenth century.

?The life of Louise Bourgeois, published author and royal midwife, is a true success story and a warning tale in one. Bourgeois?s economic future depended on staying in the good graces of the royal family. After Henri IV was killed by an assassin in 1610, she lost her royal pension but not her title and position as royal midwife. At this juncture in her life, she complained that she had lost the Paris clients who she had neglected out of necessity during the peak of her activity at the royal court. Nevertheless, she continued to write and to publish while concerning herself with building a family medical dynasty. Two more volumes of her three volume work Observations diverses appeared in 1617 and 1626, respectively. These volumes include case histories, autobiographical materials, advice to her daughter, her thoughts on the moral and spiritual role of the midwife, criticism of physicians? and surgeons? behavior in the birthing room, as well as recipes for medicaments that any housewife could make up in her own kitchen.

?Bourgeois?s daughter Marie also became a midwife and one of her sons became an apothecary. Another daughter, Françoise, married a medical student who launched a brilliant career facilitated by Bourgeois?s professional connections and the huge dowry she and her surgeon husband gave to their son-in-law. Thus, Bourgeois remarked, ?The whole body of Medicine is complete in our house.?

?In 1627, one year after the final volume of her Observations diverses was published, Bourgeois suffered a serious professional blow when a very important royal died in her care. The loss of the child sent the court physicians and surgeons into an attack mode. Their autopsy report left the impression that Bourgeois had in effect killed the baby by not removing all of the placenta from the mother?s womb, an unacceptable omission. While Bourgeois responded to the post-mortem autopsy report with great vigor, an anonymous author responded in kind, accusing the royal midwife of incompetence and insubordination. (At the time, physicians and surgeons were the midwives? professional overseers). We don?t know how Bourgeois fared after her fall from grace. However, her overall reputation seems not to have suffered outside of courtly circles. The appearance of her last publication, Recueil de Secrets (1635), published a year before her death, suggests that at least as far as her publisher was concerned, her practical wisdom was still in demand. Recueil de Secrets contains recipes for a variety of illnesses, including, but not limited to, women?s maladies.

?Louise Bourgeois?s popularity can be measured by the numerous editions of the Observations diverses that appeared in French throughout the seventeenth century, along with translations of her works into Latin, German, Dutch, and English ever since. Although her fame and the recognition of her contributions to the field of obstetrics has waxed and waned over the centuries. today she is widely recognized by historians as an outstanding woman of her time.?

Clio Notes: The author of this profile, Alison Klairmont Lingo (University of California, Berkeley), is currently writing an introduction, medical glossary and other accompanying notes for the first complete English translation (by Stephanie O?Hara) of the Observations diverses sur la sterilite. perte de fruit & foecondité , accouchements et maladies des femmes et enfantz nouveaux naiz (Paris, 1609, 1617, 1626). The volume is being prepared for publication in a series entitled ?The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe,? produced by the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Publications (CRRS), Toronto, Canada. For further information, contact

alisonlingo@gmail.com.